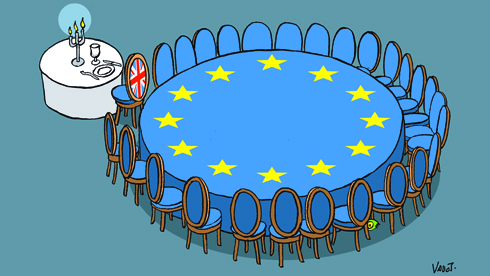

The European Union is on the verge of losing one of its members for the first time in its history. The repercussions of Britain’s departure from the bloc will ripple throughout Continental politics, economics and finances, shaking Europe to its core. Britain’s biggest EU trade partners, which stand to be especially hard-hit should Britain lose access to the common market, will desperately seek to expedite a free-trade agreement between Brussels and London. At the same time, countries in the eurozone periphery will have to brace themselves for a period of political instability and financial uncertainty that could threaten their feeble economic recoveries. Their non-eurozone peers in Northern and Eastern Europe, meanwhile, may decide to distance themselves from the bloc after losing such an important ally outside the currency area. And as the cracks undermining European unity spread, the bloc’s foundation — the Franco-German alliance — will weaken.

Analysis

Britain’s decision to leave the European Union will affect each of the bloc’s members differently. The countries that will be most damaged by the split are listed below.

Ireland

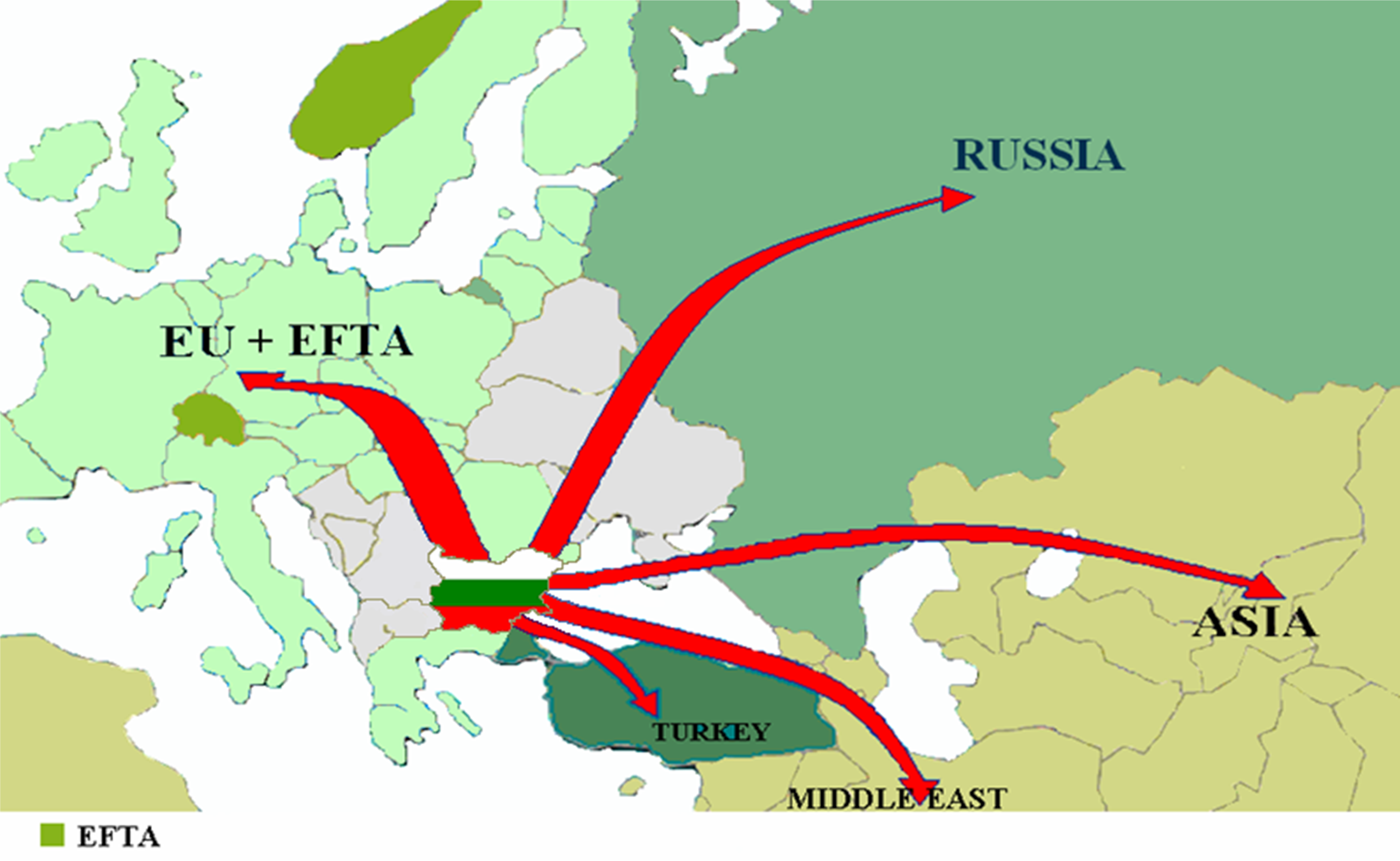

The Irish are particularly concerned by the results of the British referendum because Britain is Ireland’s largest trade partner, accounting for roughly 14 percent of Irish exports. Trade between the two will not halt immediately, since Britain will remain an EU member for at least two more years, but the depreciation of the pound will make it more difficult for Irish exporters to sell goods to Britain. Moreover, hundreds of thousands of Irish workers reside in Britain, and their status within the country will have to be defined. The referendum has also reopened questions about the status of Northern Ireland, where most of the population voted to stay in the European Union. Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland currently have open borders, but that could soon change since the Republic of Ireland will technically border a non-EU state once the Brexit is complete.

More broadly, the Brexit will force Ireland to reassess its relationship with its most important economic and political partner. In all likelihood, Dublin will become one of the strongest supporters of rapidly granting Britain access to the common market.

Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg

Like Ireland, the Netherlands will have to cope with the fact that one of its largest trading partners, accounting for some 9 percent of Dutch exports, will no longer be a member of the Continental bloc. And, as the home of the Party of Freedom — one of Europe’s strongest Euroskeptic political parties — the Netherlands will face rising demand for its own referendum on EU membership. Belgium, too, shares Amsterdam’s economic concerns, since it also sends about 9 percent of its exports to Britain. Because the country houses the European Union’s most important institutions, it has much to lose economically and politically as the bloc weakens. Luxembourg, for its part, might also experience some economic pain considering that Britain purchases roughly 9 percent of its exports as well. Of the Benelux countries, though, Luxembourg is the only one that may find opportunity in a Brexit: If British financial companies choose to relocate to the European Union, Luxembourg would be an attractive destination as one of the Continent’s last remaining tax havens.

Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece

Uncertainty in financial markets stemming from the Brexit vote will hurt the fragile eurozone economies of Southern Europe. Bond yields in Spain, Italy, Portugal in Greece will probably rise, even if they remain far below the levels seen during the 2012 crisis. The steep depreciation of the British pound may also discourage tourism in Mediterranean Europe, since British tourists will find it more expensive to vacation in the eurozone.

Meanwhile, June 26 general elections in Spain and an October referendum on constitutional reform in Italy will raise the specter of political instability in the two countries, fueling fears for their economic futures. The European Central Bank’s bond-buying program, designed to keep interest rates in troubled eurozone countries under control, was declared to be in line with German law on June 22 by the German Constitutional Court, clearing its path toward implementation. But the ruling irritated German Euroskeptics and could become a campaign issue in Germany’s general elections next year. In the meantime, Italy will have to grapple with its own Euroskeptic forces. The right-wing Northern League is already advocating an anti-immigration agenda, while the anti-system Five Star Movement has promised to hold a referendum on Italy’s eurozone membership.

France and Germany

Though France and Germany have strong trade and financial ties to Britain, their economies are diversified enough to soften the effect of the Brexit. In fact, after the dust settles, the French and German economies will probably benefit from the relocation of some companies in Britain to continental Europe. Paris and Frankfurt, in particular, will compete with each other to attract such firms.

Consequently, France and Germany’s primary concerns in the wake of the vote will be political. The success of Britain’s “leave” camp will bolster Euroskeptic parties in both countries. In France, the National Front has vowed to hold a referendum on EU membership if it wins the next presidential election, while Alternative for Germany has long supported the creation of a “northern eurozone.” With French and German general elections scheduled for 2017, the countries’ more moderate parties will feel pressured to imitate some of their Euroskeptic rivals’ proposals as they become more popular. And as the bloc’s leaders struggle to respond to Britain’s withdrawal from the Continent, the differences in their views on how to manage the European Union will be laid bare.

Poland

The Brexit will raise two major concerns for Poland. The first is the status of Polish citizens working in Britain. Since Poland joined the European Union in 2004, about 1 million Poles have migrated to Britain. How they will be dealt with will be determined by whatever deal London and Brussels reach on the status of EU citizens living in Britain. London is unlikely to start deporting people en masse, but it could put in place strict requirements for obtaining and keeping work permits. Even if Britain agrees to allow EU citizens to remain within its borders, an economic downturn with the loss of jobs could force migrant workers to return home. Poland, and other states whose nationals have migrated to Britain in large numbers such as Romania, Bulgaria and Lithuania, will therefore advocate a quick resolution on the status of EU citizens in Britain.

From a political standpoint, Warsaw will lose an important ally in the bloc. The Polish government was one of the biggest supporters of British Prime Minister David Cameron’s calls to repatriate powers from the European Union to individual members and to give national parliaments greater room to veto EU regulations. The British vote, in theory, has opened the door for Poland to make similar demands itself under the threat of a Polish referendum. However, Poland cannot afford to leave the bloc, so any threats it makes to Brussels would have to be made in concert with its neighbors to be considered credible.

Hungary and the Czech Republic

Hungary and the Czech Republic will lose a key political ally as well. Britain is widely seen in Central and Eastern Europe as a defender of the interests of non-eurozone states. Budapest is especially supportive of London’s view that the European Union is an accord made among sovereign nation-states Neither country is likely to leave the Continental bloc anytime soon — it is a crucial source of funding, and the Czech and Hungarian populations are supportive of EU membership. But both nations might hold referendums on specific EU issues. Hungary, for instance, has already announced that it will hold a vote on the controversial EU plan to redistribute asylum seekers across the Continent.

Sweden and Denmark

Britain often voted alongside Sweden and Denmark on EU policies. The three countries shared an interest in preserving the common market while resisting attempts to federalize the bloc. Denmark and Britain negotiated their opt-outs from the eurozone together in the early 1990s. Not long after, Sweden followed suit, choosing not to join the currency area.

Sweden and Denmark’s relatively strong Euroskeptic forces could be emboldened by the British referendum, enough so to call for similar votes in their countries. And as Britain’s departure upsets the balance of power in Europe, the Continent’s northern members might decide that the time is ripe to re-evaluate their relationships with the bloc.

Cyprus and Malta

Cyprus maintains strong bilateral ties with Britain, a legacy of the island’s British colonial presence. Britain is Cyprus’ second-largest trade partner, and the island, in turn, is a popular destination for British tourists. Malta similarly boasts a deep historical relationship with Britain, and it is home to numerous British companies, many of which are in the financial sector. Britain’s divorce from Europe will therefore be a blow to both islands’ trade, finance sectors and tourism.