BY: ANDREA GARCIA RODRIGUEZ

The 2014 Indian elections are already a reference point in the marketing world for the remarkable materialization of Narendra Modi as a brand. As David Aaker explains, the recipe had three main ingredients: making a regional brand national, cleaning the dirty past and connecting with urban and young voters, for in 2014, 150 million Indian people would have voted for the first time. These three lines were supported by extensive literature and propaganda, even featuring comic books where guided by a heroic behavior, a young Modi would save animals, pray in the temple or would prepare Ayurvedic medicine for his mother.

His many successes as the Chief Minister of Gujarat gave him the necessary political prestige. Touted as a good administrator with vivid ideas on development and economic growth, he won his nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) the majority in the lower chamber of Parliament; a feat that has not happened in 30 years. Almost four years have passed since, and Narendra Modi continues to be the most popular Indian leader, with 88% on average favoring him, exceeding 90% in the Southern statesand even in Punjab, where the majority of the population profess the Sikh faith.

Data from the Pew Research Centre and the World Economic Forum revealed that only a year after the 2014 election most of the country believed India was on the right track, a still-present upward trend, versus the 29% existing in the pre-Modi era. Before Modi took office, India’s political scene was a sum of the Congress Party, the left who sought to represent the impoverished segments of society, and the BJP, apostles of Hindutva. The vacuum of power generated by the declining morale and appeal of the Congress Party amid the corruption scandals was the perfect breeding ground for the BJP victory in 2014; a party that rules in 19 out of 29 states after the Gujarat elections of December 2017.

The BJP has always criticized the secular policies of the Congress Party, advocating for the establishment and recognition of the Hindu culture for India. Accordingly, one of the landmarks for the party was in 1992 when the demolition of the Mosque of Bābur, where the concept of cultural nationalism overtook the ideological nationalism. The fall of the Babri Mosque, which was located in an area considered sacred by Hinduism, was the culmination of the Ram Janabhoomi (literally translating to Ram’s birthplace) movement with many BJP leaders at its helm. Albeit the party, due to criticism, later conceived Hindutva as a renaissance – abstract, engaging, to be developed organically – and less as a goal to be achieved by active means, the fall of the mosque marked a decisive shift towards identity politics. Since then, the lack of a serious condemnation of violence towards minorities by PM Modi was even noticed by then-President Barack Obama in 2015, who condemned the persecution of people “for their beliefs and heritage” in recent times. Modi, whose unapologetic attitude towards the 2002 Gujarat riots that saw the death of thousands, resulted in him being denied entry into the United States.

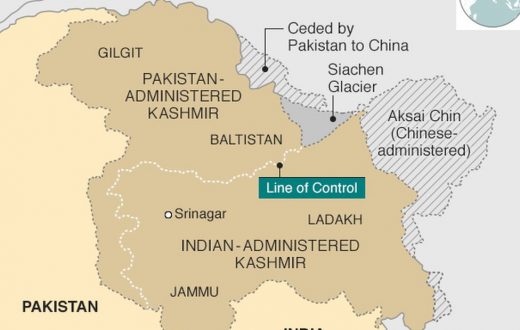

The vision that Narendra Modi has for the domestic India is complemented by international projections of power. He sees the military as a way to modernize and strengthen the country, as well as a strategy to counterbalance the growing presence of China in the region, directly affecting the country by its northern border. Since Modi took power, military expenditure has expanded by an average of 10% per year, recently making India the 5th country in the world with the highest investment in the military. This trend breaks with that of the previous administrations that increasingly cut the budget allocated to this sector.

Moreover, the Prime Minister has also become the champion of the fight against corruption. The demonetization strategy of November 2016 left the 86% of the circulating banknotes useless overnight when all 500 and 1000-rupee bank notes were declared null. This measure sought to eliminate fake currency and force people to pay taxes, as well as a transition to digital money – though the latter was more of an organic reaction to the measure than one of the stated objectives. While some hailed demonetization as a genius move, others have pointed out its crippling effects on the lower classes. The impact of such policy continued to remain high as India still remains a cash-based economy. However, Modi’s brand of success masks the threat his rhetoric poses to the very foundations of democracy.

One can be a great manager, a superb speaker and a devoted Democrat. However, democracy implies the respect, recognition and admiration of the role of the opposition. “Congress-Mukt Bharat” is the slogan Modi used in the 2014 elections to attack India’s Congress Party and that has been recently revitalized by the BJP leader. Modi defends himself by labelling “Congress” as synonymous with a culture of corruption, of treachery and of casteism that seeks to keep complete control over power. His claim has been identified as a general call to end the Congress Party by its explicit reference and impossible-to-miss background of use. To define the opposition as dissidence, in the words of former Czech President Václav Havel, is the first step towards authoritarianism.

Were the BJP of Narendra Modi to obtain the majority in both chambers of the Indian parliament after the 2019 general elections, the new wave of nationalism could endanger the quality of Indian democracy, statically rated as 77/100 by Freedom House every year for, at least, the past decade. Provided that this brand of Hindu nationalism gains enough support to continue its ride in front of the executive, the minorities would surely have a tough time ahead. Religious violence could increase being the ratification of the BJP’s initiatives shown in the chambers, and its ideas could expand to India’s area of influence, namely, Southeast Asia, especially in fellow Hindu countries such as Nepal. Multi-ethnic, multi-religious and multilingual India, should not compromise its values and consolidated Democracy for an ideology that aggrandizes one group over another, for nationalism, quoting Tom Nairm in 1977, is “the pathology of modern developmental societies […] a similar built-in capacity for descent into dementia”. Let India react and correct this drift before it is too late.

Andrea G. Rodriguez is an international security analyst. She holds a B.A. in International Relations from the Complutense University of Madrid. She has been part of several mobility programs, including at Charles University in Prague, where she studied Geopolitics and International Security, and at the National Taiwan University, where she focused on Asian security issues.

This article was originally published by Political Insight and is available Here.