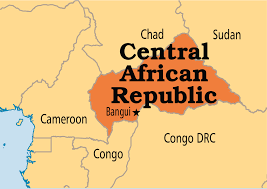

The Central African Republic’s (CAR) postcolonial history has been dominated byconflict. From the disastrous rule of Jean-BedelBokassa, through President André Kolingbaand then Ange-Félix Patassé, the CAR ultimately came to the Bangui Agreements, which aimed to resolve widespread social and economic grievances. Since then, the most important of CAR peace effortswas the Global Peace Accord, signed initially by the ARPD, UFDR, and FDPC groupsin Libreville, Gabon in June 2008. It granted amnesty for acts against the state prior to the agreement, and called for a disarmament and demobilization process to reintegrate former rebels into society and the regular CAR armed forces.

Other rebel groups signed on to the agreement later or signed similar agreements, as was the case for the UFDR in December 2008. The only major group not to sign was the CPJP, which continued on until signing a peace agreement with the government in August 2012.Prior to that, the CPJP and UFDR continued to fight over control of artisanal diamond fields in western CAR, especially around Bria. The CPJP announced that it was ready to end fighting and signed a ceasefire deal, but violence resumed and more than 50 deaths were reported in September 2011. A CPJP-UFDR deal that October, signed in Bangui, called for the demilitarization of CAR’s Bria region.

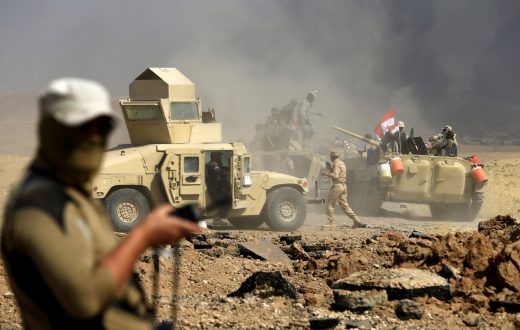

That history leads to conflict in CARthat again intensified in 2012 when disparate Muslim groups in the country unified under the banner of the Séléka movement. Angered by the exclusionary rule of President Francois Bozize’s administration, Séléka militias overthrew him despite pleas for help from France.TheSélékamovement tried to fill the resulting power vacuum by appointing Michel Djotodia as president. Large-scale sectarian violence broke out as Christians in the country formed their own Anti-Balaka militias and attacked Muslim civilians in Bangui and other provinces in the country. More than 1 million Muslimcivilians fled the capital into the CAR north and to Chad and Cameroon in 2013.

The Sant’ Egidio peace agreement

The most recent CAR deal came in June, when the government of President Faustin-Archange Touaderaand more than a dozen armed groups inked an agreement mediated by the Roman Catholic Community of Sant’Egidio. It briefly raised hopes forpeace based on three main points – the political situation and ceasefire, security and economic issues, and humanitarian and social issues. The very next day, hopes for the agreed-upon commitments and “a dynamic of reconciliation” ended in the gunfire of heavy fighting between Séléka and Anti-Balaka forces at Bria and elsewhere in the north. It seems obvious that “getting an agreement” to end the war is an illusion.One wonders why these deals brokered by the UN or western powers so often fail to be implemented once they’ve been negotiated, in CAR particularly.

Former Prime Minister Martin Ziguélé, a widely respected CAR economist, argues that peace agreements can work with the commitment of all parties and careful follow-up by experienced leaders.

Peace agreements or protections to end the civil war?

Perhaps the most significant reason for the recent escalation of violence lies within Touadéra’s government. The new president, who was Bozizé’s prime minister, has relied heavily on former Bozizé ministers to build a new government and – as Stratfor analysts note – reform security services and reintegrate former militants. It’s resented by militant groups who wanted change in 2013, and given the anemic CAR leadership may lead to another coup in the near future.

The transitional government in CAR headed by Catherine Samba-Panza was supposed to restore order and security, protect the population and start putting the country together while it was falling apart. Yet hostility and resentment increased, and the ethnic tensions deepened as armed groups fragmented, multiplied and became increasingly criminalized. The transitional government was a fiasco, and the international community should have ended the mandate of the transitional institutions after one year, replacing them with more professional people and a real strategy.

Former minister Marie-Reine Hassen, a widely respected Central African economist and ambassador,argues that a rush to elections was too dangerous and risked more atrocities, but the advice wasn’t heeded and those elections added fuel to the fire. The months-long surge of renewed violence followed in the aftermath, but there are a number of factors that make a working peace deal elusive.

Hassen doesn’t believe in peace agreements in CAR at all. Forums, gatherings, summits and peace conferences don’t deliver results on a crisis she connects to human rights violations and impunity. Rebel groups committing serious human rights violations, some of which may constitute international crimes, are never held accountable in each successive wave of peace deals. No dialogue has ever brought any peace. Negotiations were never the solution. Now the situation has worsened as the new government is completely unable to control the territory and ensure public order and security, but it’s precisely the rule of law and the end of impunity that Hassen views as the only win-win solution.

What’s really fueling the CAR crisis

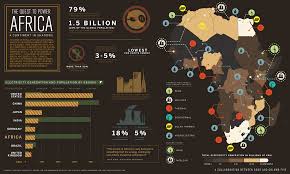

For his part, Ziguélé looks at economic and financial reason. “The leaders of armed groups are looking to control areas of economic interests, mining sites and cattle breeding areas, in order to feed their activities,” he says.“The struggle for this control has opposed armed groups between them for many months with collateral victims among civilians.” Yet this moment in the CARconflict seemsthe most destructive in its violent history, and is a result of the failure to fully invest in lasting peace agreements.

Ziguélé argues that strong security measures are needed to convince both Séléka and Anti-Balaka fighters to leave the armed groups, but Hassen adds that the recent conflict has shattered what remained of an economically devastated state. Anger over disparities, real or perceived, in the Muslim and Christian groups are triggered by economic issues, and sectarian motivations are very apparent.

Hatred of the Sélékas degenerated into anger at all Muslims from Christian Anti-Balaka groups as the violence spreads. Their ranks, as well as those of the Séléka armed groups that overthrew Bozizé, have fractured into armed bands scattered across CAR carrying out equally vicious attacks, fighting has also increased in the central and eastern provinces of the country, and apart from the frequent attacks on UN peacekeepers and humanitarian workers, the world isn’t paying attention anymore.

Finding a peace process that works

Some Séléka fighters say there’s no place for the international community if Touadéra fails to initiate a national dialogue with all CAR actors.On the other hand, Ziguélé thinks international actors have to play a great role on peace agreements, beside African and regional actors. Yet, as Hassen notes, neither the UN, nor the African Union, nor the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) has prevented the CAR collapse and its ongoing disintegration. Mediation by Congo-Brazzaville President Denis Sassou Nguesso made the conflict worse, and targeted sanctions don’t help.

Mediators may do more harm than good, but the main responsibility for protecting the CAR from mass atrocity crimes lies with the government of CAR, and that means a stronger leader than Touadéra may be necessary. If the security dilemma is addressed through a clear, credible and extensive commitment in CAR, by external forces (China, USA and France) that adequately deal with spoilers and power sharing, careful mediation can deliver a peace deal. Regional powers including Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon, Chad and perhaps Sudan need to play a role, but that won’t happen if peace processes are manipulated by elites or other interest groups with in CAR. It’s only when the country itself comes to an agreement that peace might be achieved.