Oil prices hit their lowest level since summer 2004 this week, continuing the rapid shift that began in July 2014. The global benchmark, Brent crude oil, closed trading Jan. 8 at $33.37 per barrel, closing out the lowest week of prices in more than a decade. A number of factors contributed to the drop. The Chinese economy and financial markets performed poorly this week,sparking fears that a slowdown will dampen demand.

Oil is the most geopolitically important commodity, and the ongoing structural shift in oil markets has produced clear-cut winners and losers. Between 2011 and 2014, major oil producers became accustomed to prices above $100 per barrel and set their budgets accordingly. For many of them, the past 18 months have been a period of slow attrition. And with no end in sight for low oil prices, their problems are going to only multiply. Each nation, though, has its own particular level of tolerance, and the following guidance highlights the key break points to monitor.

Former Soviet Union

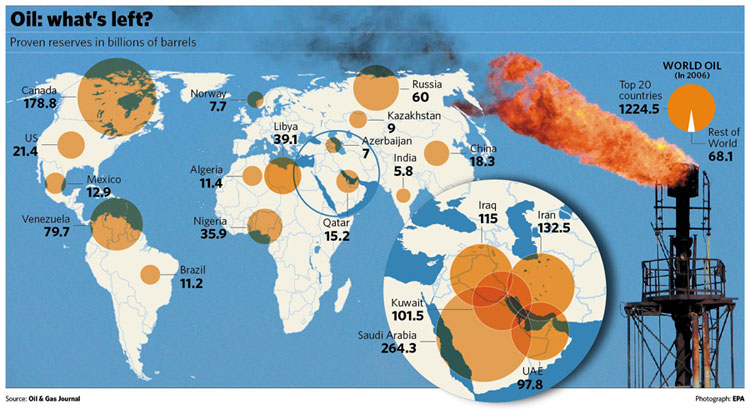

Russia, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan stand to lose the most among the countries of the former Soviet Union. As one of the world’s largest producers, Russia is the most important. Russia’s economy relies heavily on energy, and energy revenues constitute more than half the current budget. This budget, however, is calibrated to oil prices of $50 per barrel. As prices deviate further from this benchmark, Moscow has two funds totaling $131.5 billion to make up the discrepancy. But the margins are tight: Nearly half the amount on hand may be needed to cover 2016 budgetary shortfalls even if oil rises to $50 a barrel.

To remain afloat, the Russian government would have to drain both of these funds unless it cuts the state budget. Cuts would come with major tradeoffs. Moscow is embroiled in a standoff with the West, so slashing defense or security spending would be challenging. Russia will also hold critical parliamentary elections in September, so cutting social programs is not a good option either. Compounding this dilemma, Russian oil firms are in dire straits; although the government could restructure the tax system to provide them with relief, it would undermine government revenues. Moscow also has the option to privatize a large part of state-owned oil giant Rosneft this year to raise funds.

Both Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan face dilemmas similar to that of Russia. Kazakhstan’s budget is set at $40 a barrel, although it does have $55 billion in its national oil fund. An alternative budget is now being drawn up based on $20 a barrel, but such a change will almost certainly mean cuts in spending. Like Russia, Azerbaijan’s government set its budget based on $50 a barrel. Azerbaijan holds $51 billion in its state oil fund. Both countries are concerned with rising social tension over their weakening economies, although their governments have proved adept at cracking down on dissent. Kazakhstan plans to privatize state-owned companies and assets to raise money in 2016, though there has been little interest in the program among potential buyers.

Middle East and North Africa

Regionally, Algeria, Iraq and Iran, the oil-producing Gulf Cooperation Council states, will feel the most impact from low oil prices. For 2016 government budgets to break even, the International Monetary Fund projects that Saudi Arabia will need oil prices of $98.3 per barrel. Bahrain will need prices of $89.8 per barrel and Oman of $96.8. All are significantly higher than the break-even points of Kuwait, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. For the most part, however, the Gulf Cooperation Council nations are in a position to weather low prices, since they hold low levels of debt and high financial reserves built up from years of high oil price revenues. Although Bahrain is an exception to this because it is not a major producer, Riyadh would sustain the country through a crisis to prevent spillover into Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province.

In the short term, the Gulf Cooperation Council will not fall into financial crisis, but its member states are still making the financial adjustments needed to keep their reserves high and to avoid going deeper into debt. All of the Gulf nations will cut government spending in 2016 to some degree, albeit carefully, and will accelerate legal reforms. To ease the burden on citizens, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are reducing fuel subsidies but maintaining spending on education and social services. Bahrain has reduced food subsidies but is considering cash handouts to balance the cuts. The United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar and Kuwait are all discussing implementing taxes to increase state revenue, a measure unprecedented in the regional bloc.

Saudi Arabia is the most important country to watch. In addition to the careful cuts in social spending, the government has already started to privatize assets, starting with three major airports. Riyadh has even discussed floating a part of state-owned Saudi Arabian Oil Co., known as Saudi Aramco, in an initial public offering. Privatization will diversify the funding sources of these entities but also is politically risky. Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has hinted that reforms may be rapid, even as the king emphasizes the strength of the economy, but powerful members of the Saudi royal family will be wary of moving too swiftly. With dozens of privatization plans on the table, discontent within the ruling family is all but inevitable. Riyadh is also facing major regional changes with the return of Iran to the international economy and the enduring conflict in Yemen, meaning that defense and foreign spending will need to remain high.

Not all regional players have the fiscal advantage of the Gulf Cooperation Council. Algeria’s economy is highly dependent on natural gas, and its foreign reserves dropped precipitously in 2015 because of lower oil export revenue, leading to a $10.8 billion deficit. A mild winter in Europe, a key market for Algerian natural gas, will not help the situation. Algeria has sought to boost foreign investment through tax reform and the introduction of import and export license authorizations. But the country is heading toward a precarious political moment: the eventual death of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who has held office since 1999. The nation’s elite are now jockeying for position ahead of this transition; although continued reform measures are necessary, many will be wary of any that may erode their power. This will limit the country’s options, compounding the current crisis.

In Iraq, both Baghdad and the Kurdish capital of Arbil are already in serious financial trouble. The national government and the Kurdistan Regional Government need to maintain high levels of spending to fund their battle against the Islamic State. With oil revenues dropping, this means they will need to reduce other expenditures. The governments do have the option of renegotiating their contracts with international oil companies. Baghdad is in the midst of such talks to replace its current contract, which stipulates that Baghdad pay oil companies a fixed fee. Arbil is juggling its security situation with payments to international oil companies and the giant Kurdish civil service sector. The Kurds have already made it clear that they have no plans to export oil through Baghdad’s state-owned marketing company but will instead market it themselves and export through Turkey. Ankara and the Kurdistan Regional Government in Arbil will grow closer as both increase energy cooperation and deal with the mutual threat of the Islamic State. Arbil’s increased suffering under low oil prices will only strengthen this relationship.

Amid low oil prices, February elections are also approaching in Iran. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani will be banking that his talks with the West and success in negotiating the end of sanctions will help moderates and his traditional conservative allies defeat hard-line conservatives. The opposition has asserted that Rouhani’s economic policies are not working. Low oil prices will make these arguments only more credible. The end of sanctions will enable Iran to increase the volume of its exports, but with prices down nearly 70 percent since 2014 the revenue generated will not reach the level it would have two years ago. This realization may not become clear to voters until after February elections, meaning Rouhani could perform well. But by 2017, the discrepancy will likely be obvious, jeopardizing his chances for re-election in 2017.

Latin America

Oil-dependent and ailing Venezuela will suffer a great deal because of sustained low oil prices. Annual inflation is already at nearly 300 percent according to leaked central bank estimates. Inflation will mount and shortages will become even more extreme. Lower oil export revenues will reduce the country’s expenditures not accounted for in the budget, which in 2015 supplied much of the additional foreign currency needed to finance imports and foreign debt payments. Venezuela will likely need to decrease imports, and the country could even default on its foreign debt later in 2016. In the near term, the government, now with an opposition supermajority, will take what steps it can to address the economic situation. Currency devaluation and consumer price hikes would be the most effective remedy, but these would come with unacceptable political costs. Further unrest is inevitable, and the government will need to work to contain this from spreading too widely.

Brazil’s economy has already sustained a great deal of damage from the corruption scandal in state-owned energy firm Petrobras. Unless the government decides to curb the major criminal investigation into the company and associated officials, the scandal will continue to disrupt supply chains and contractor financing, further delaying existing projects. In response to the disruptions, Petrobras will need to further cut its investment plans, which will slow future foreign investment and energy production.

Ecuador’s oil exports plummeted by 30 percent in 2015 and will continue to be low through the next year. Quito has the option of imposing trade barriers to reduce imports and to compensate for lower export revenue, but this would compound the economic slowdown. The nation will hold a presidential election in February 2017, which could highlight eroding public approval for the ruling Alianza Pais coalition because of the declining economy.

North America

North America has, of course, been under the same low oil price pressure as the rest of the world. Nevertheless, production has been resilient in recent months, staying at around 9.2 million barrels per day since October. Production has the potential to fall again, however, as the oil hedges taken out against low oil prices in 2015 expire. The remaining 2016 hedges are mostly at a lower volume or price, a fact that will increase the burden on oil-producing companies. Across the continent, companies have drilled numerous new wells, but companies are holding off for higher prices before they complete the projects. This means that there is spare capacity that can react if prices make a sudden leap. As Iranian oil comes back on the market, if North American production remains high, it could exert more downward pressure on prices. Producers of heavy oil in Canada in particular are going to remain under more pressure as Western Canadian Select, the Canadian heavy oil benchmark, is already well below $20 per barrel.

Sub-Saharan Africa

The portion of Africa below the Sahara Desert is home to numerous small oil-producing countries that will feel the pinch of low oil prices to different degrees. The continent’s largest economy and oil producer, Nigeria, will be affected the most. Unlike producers in the former Soviet Union and in the Middle East, Nigeria has calibrated its budget using the rather realistic price of $38 per barrel. The problem is that even at this price point, the budget will run a deficit of $11 billion, 2.2 percent of GDP. Abuja will find it difficult to maintain its fuel subsidy programs and its currency peg to the U.S. dollar, put in place in June 2014 when the naira fell 25 percent. Since that time, the gap between the official and unofficial currency exchange rates has widened. Low oil prices will only make it wider. The new president, Muhammadu Buhari, has been clear that he does not support devaluation but will face pressure from various political interests and will likely need to cut spending.

Angola, Africa’s second-largest producer of crude oil, is under the same financial pressure as other world oil producers. The government, however, is quite stable. The ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) has tight control of the state security apparatus. Any threat would have to come from within the party itself. The government has based its 2016 budget on $48 per barrel oil prices and is continuing the large-scale austerity programs it began in 2015 in response to the initial drop at the end of the previous year. Angolan President Jose Eduardo dos Santos is now contemplating whether to step down in 2017. Power brokers within the ruling party are competing to become his successor, and low oil prices will make this competition more heated simply because there will be less money to pour into patronage networks.

Asia-Pacific

Most Asia-Pacific countries are net consumers of oil rather than net producers. This means that much of the region stands to benefit from low oil prices. However, there are two exceptions: Malaysia and Indonesia.

As one of the few net producers in the Asia-Pacific, Malaysia will feel the greatest pressure from cheap oil. Last year, roughly 20 percent of the Malaysian government budget came from the earnings of state-owned oil company Petronas. As the firm’s earnings declined, Kuala Lumpur was forced to impose an unpopular goods and services tax to make up for the shortfall. The government’s 2016 budget has Petronas contributing less than 12 percent of federal income. If oil prices continue to plunge, however, Malaysia will have to find new ways to raise money, either new taxes or pared-down services and subsidies. This will make the government unpopular at a time when Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak is mired in a corruption scandal involving the country’s sovereign wealth fund, 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB). Since the political opposition in Malaysia is still incoherent, those who stand to gain from Razak’s declining public support are probably his rivals in the ruling United Malays National Organization.

To the south, Indonesia will find low oil prices to be a mixed blessing because the country is a net consumer of oil but a net producer of natural gas. Natural gas revenue will certainly drop, which will hit state and export revenue. But low oil prices will give current President Jokowi Widodo a chance to continue delaying unpopular gasoline and diesel subsidy cuts. When Jokowi came to office in 2014 he cut fuel subsidies, bringing domestic prices to international levels. But as prices rose during the course of the middle of 2015, he declined to raise consumer prices and instead had state-owned Pertamina sell imported products at a loss. Now, with prices still dropping, Jokowi may be able to avoid the issue of raising prices and instead may cut them.

Europe

Much like the Asia-Pacific region, low oil prices will be largely a boon for Europe because most countries are net oil consumers. Norway, theContinent’s main oil and natural gas producer, will not be so lucky. The country is in the middle of an economic slump due in no small part to a drop in oil-related investment and activities in Norway. According to the International Monetary Fund, Norway’s GDP growth fell to 0.8 percent in 2015, down from 2.2 percent the year prior. Over the same period, unemployment grew from 3.5 percent in 2014 to 4.2 percent in 2015; this figure is expected to rise even further in 2016. Though the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development projects a gradual economic recovery for Norway in the next two years, the trajectory of oil prices could impede this.

In the long run, low oil prices could also cause problems across the Continent as a whole. Presently, they are improving Europe’s economic climate; this could lead Europeans to believe that they are witnessing a “real” recovery when in fact a sizable share of the progress is caused by external factors. This misperception could play a particularly significant role in Southern Europe, where governments are beginning to slow reform efforts. Additionally, reduced oil prices could work against the European Central Bank’s attempts to create inflation in the eurozone in the hope of boosting economic growth in the bloc.