The U.S. Federal Reserve announced Dec. 16 that it will raise short-term interest rates to 0.25-0.5 percent from the current 0 to 0.25 percent, citing favorable economic conditions, according to an official press release from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The board voted unanimously in support of the measure and the decision was also accompanied by an official announcement that the U.S. rate hike path would be “gradual.” The Fed has kept interest rates, and therefore borrowing costs, low since the 2008 financial crisis and the hike is a reflection of the solid, sustained growth of the U.S. economy over the past few years.

This decision and its scale are historic and unprecedented in American History.

Analysis

Over the past few days, two U.S.-backed rebel groups in Syria have been fighting pitched battles in northern Aleppo. But rather than battling the Islamic State or Syrian loyalists, the rebels have been fighting among themselves. The skirmishing between the Marea operations room, a coalition mainly comprised of Free Syrian Army units that hold positions against the Islamic State in northern Aleppo, and the Jaish al-Thuwar rebel group, which is a part of the Syrian Democratic Forces, threatens to undermine international efforts to utilize rebel factions to drive the Islamic State out of the area. To make matters worse, the local conflict has the potential to spread, enveloping the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, better known by the acronym YPG.

Both rebel groups have substantially different narratives about how the fight broke out early last week. Jaish al-Thuwar says the conflict started when al Qaeda-linked rebel group Jabhat al Nusra attacked it near the town of Azaz in northern Aleppo on Nov. 23, forcing Jaish al-Thuwar to defend itself. But the Marea operations room denies that claim, instead saying that Jaish al-Thuwar attacked its positions with the support of the Kurdish YPG and the Russian air force — something Jaish al-Thuwar vehemently denies. Over the weekend, Free Syrian Army units aligned with the Marea operations room managed to gain the upper hand in the fighting, aided by Ahrar al Sham. However, the conflict is expanding and may soon fully include the Kurdish YPG.

The Kurdish YPG is an active ally of Jaish al-Thuwar in the broader U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces coalition. The Syrian Democratic Forces have achieved considerable success fighting the Islamic State east of the Euphrates River, but have only recently begun operating in northern Aleppo in any meaningful way. The entry of Jaish al-Thuwar into northern Aleppo, along with its strong links with the Kurdish YPG, have marked it as a competitor and a potential threat to well-established Free Syrian Army units operating in the area, as well as to more extremist Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al Nusra factions. This mistrust has fueled the tension and subsequent fighting between the two sides.

Like the Americans, the Turks were hoping to push the Islamic State from the Marea-Jarabulus line, utilizing the Free Syrian Army units of the Marea operations room, as well as the Syrian Democratic Forces. Turkey, while uneasy about Jaish al-Thuwar’s relationship with the YPG, appeared willing to allow the group’s participation in the operation as long as the YPG itself is excluded from any action in the Marea-Jarabulus zone west of the Euphrates. The infighting between the rebels in Aleppo, however, threatens the fight against the Islamic State: The rebels are turning to focus instead on each other, and the YPG is increasingly supportive of its Jaish al-Thuwar partner.

The Turkey-Russia Complication

Meanwhile, Russian aircraft are intensively striking rebel supply lines on the Turkish border in northern Aleppo, working to close the Syria-Turkey border in retaliation for Ankara’s downing of a Russian jet Nov. 24. The Russian air force’s active presence in northern Aleppo threatens the planned operation against the Islamic State in the Marea-Jarabulus zone, raising the risk of a confrontation between Russian aircraft and Turkish warplanes supporting the operation.

Nevertheless, Turkish armed forces are increasing their presence on the Syrian border with Aleppo province, south of the Turkish city of Gaziantep. The Turkish air force moved additional fighter jets to its airfields near Syria, while Turkish ground forces dispatched reinforcements, including tanks, to support forward elements on the border. The Greek media also reported that Ankara has moved troops, tanks, and artillery from the 1st Army — tasked with guarding Turkey’s borders with Greece and Bulgaria — to the border area north of Aleppo. Turkish officials continue to state that an operation against the Islamic State in northern Aleppo is going to take place.

Ankara has long been pushing for such an operation in order to drive back the Islamic State from its borders, strengthen Turkey’s rebel proxies in Syria, and further contain perceived Kurdish expansionism. Yet with rebels fighting each other, distracted in their efforts to stop loyalist advances elsewhere in Syria, it is increasingly likely that the Turks will need to commit ground forces to push the Islamic State back.

Faced with this prospect, Ankara has to decide whether to further postpone the operation being planned with the United States or to cancel it completely. Turkey could proceed with a modified operation that includes a greater role for its armed forces, but this would risk not only its troops in battle against the Islamic State but also the hazards of friction and potential escalation with Russia. Turkey needs to drive the Islamic State from the Marea-Jarabulus line, but rebel infighting and the looming Russian presence complicates Ankara’s plans enormously.

Islamic State militants conducted a prolonged mortar attack against a military training base in northern Iraq, where Turkish advisors are ‘training’ militia forces-Mostly Turkmen-. According to Iraqi authorities, two young Turkmen died and several more were severely injured in the attack that lasted three-hour. Reports about Turkish casualties remain unclear. Turkey reportedly has been training Turkment and possibly Peshmergas and other volunteer forces in the Kurdish-controlled regions of Iraq since November 2014, but created tensions with Baghdad after dispatching 300 troops to the area around Mosul on Dec. 3.

In Damascus , the cold night of December 19th was not any different from the others nights in Damascus. The streets were full of people and cars despite recurrent electricity blackouts. The coffees were full of clients , despite the civil war and large groups of foreign journalist were staying at the Sheraton Hotel. Few blocks away, Samir Kuntar , a terrorist that killed a whole family in Israel in the 80s , and has since became a Lebanese commander of “The Syrian resistance for the liberation of occupied Golan” was at his residence in the suburb of Ja’aramana in the eastern part of Damascus.

At 22:42 p.m., Twitter account “Damascus Now” tweeted: “Several mortars exploded in the city of Jaramana injuring several people.” This was to be normal, too, if it wasn’t for the fact that what was thought to be mortars were missiles that destroyed the building and killed three men.

Most of the local resident know that Kuntar lived in that building according to local sources.

A local journalist declared for local newspapers: “They found the body, told the family, and it’s now all about Hezbollah’s statement in the morning.” At 4:18 a.m., Bassam Kuntar, Samir’s younger brother, tweeted the news: “With honor, we mourn Cmdr. Samir Kuntar and we proudly join the cavalcade of the martyrs’ families.”

Samir Kuntar knew that Israel wanted to retaliate against him, and as a consequence knew his days were counted. He even declared to the Pan-Arab news network Al-Mayedeen few months before that “The most important thing is that even if Israel assassinated me, the path of resistance in Syria started and nobody can stop it.”

Kuntar discussed the issue with close friends and raised it with his leaders in Hezbollah.

“The Israeli threats on martyr Kuntar’s life existed from the day he was released, even before the issue of the popular resistance in the Golan Heights was discussed,” Hezbollah’s Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah said in a speech on Dec. 21, mourning the man whom he described as “one of us,” and vowing revenge. “It’s our right to seek revenge and we will practice this right — let this be known to everyone,” Nasrallah declared

Hassan Nasrallah, the spiritual leader of the Chiite movement Hezbollah spoke in a relatively calm manner, in comparison with its other speeches were he call to destroy the “Zionist Entity”. He declared: “There’s no doubt that Israel carried out the assassination. It was a roaring military operation, not a silent ambiguous intelligence attack,” he continued: . “I’ll repeat what I said in January 2015: Whenever any cadre from the Islamic resistance is killed, we will hold Israel responsible and we will respond.”

Hezbollah has been engaged in a paralled war on different fronts with Israel, the newest one being the Golan front , which he referred to in his speech. The assassination of Kuntar seems to be part of this parallel war.

But Hezbollah which is also engaged against Sunnis rebels in Syria, is also facing large opposition among the Sunnis in Lebanon and also in Syria. These recent months, Hezbollah Strongholds in Beirut have been the theaters of various suicide attacks , that targeted clearly Shiites. These attacks were not carried out by Israel but by Sunnis Rebels, from Al-Nusra and ISIS.

Kuntar, according to an Israeli and Iranians, had been working on building the “Syrian resistance for the liberation of occupied Golan” since May 2013. That means he was clearly planning attack against Israelis in the Golan.

Thath is the main reasons why Kuntar was sent by Hezbollah to Syria. There he started to work on old plans to create a new front on the Golan that will makes the headlines in the newspapers. He was supposed to continue the legacy of the former Hezbollah military commander Imad Mughniyeh , that was killed in a targeted killing by Israel in February 2008.

According to our Israeli sources: Kuntar worked on building cells from residents of areas close to the borders with the Golan Heights. He worked on providing them with training, arms and salaries”. His group was getting bigger; his first local officer was called Moafak Badriyeh, a Syrian from the village of Hadar from the liberated part of the Golan Heights. Badriyeh was later killed by Israel. He was responsible for launching rockets at Israeli posts in the occupied Golan Heights and bomb attacks.”

In March 2014, three major incidents took place in the Israeli-occupied part of the Golan Heights: an attack on March 5, March 14 and March 18. The last attack saw one Israeli soldier killed and seven wounded, while four were injured during the second attack.

On April 26, four Syrian fighters were killed during a clash with an Israeli patrol in the Golan Heights. A statement issued that afternoon by the popular Syrian resistance read: “Four Syrian resistance heroes were killed Sunday evening, April 26, 2015. Two from Hadar — Youssef Hassoun and Samih Badriyeh — and two sons of the martyr prisoner Walid Mahmoud from Majdal Shams, Nazih and Thaer Mahmoud.”

An Iranian military source told Al-Monitor that efforts to build the Syrian resistance was a main task executed by Kuntar in coordination with Hezbollah and under the direct supervision of Iran’s Quds Force commander Maj. Gen. Qasem Soleimani and Nasrallah.

“This was an ambitious strategic project for the resistance bloc, and Kuntar played an important role in making it happen. He was assassinated by Israel and he already planned his own revenge,” the source said.

In January 2015, five Hezbollah members and an Iranian high-ranked official were killed in the Golan Heights near Quneitra, when the Israeli Army launched an air-attack on their position. The Israeli Defense forces eliminated in the strikes very important Hezbollah’ leaders Jihad Mughniyeh, the son of Hezbollah’s slain commander Mughniyeh, and Mohammed Issa, who is said to be the Hezbollah commander responsible for the Golan front.

On Sep. 8, the US State Department designated Kuntar as a “specially designated global terrorist.” According to a statement published on its website, Kuntar “played an operational role, with the assistance of Iran and Syria, in building up Hezbollah’s terrorist infrastructure in the Golan Heights.

All the attention is now concentrated on the next Nasrallah’s speech to see if Hezbollah is willing to respond and how. Hezbollah did not rule out to use legal options, but military retaliations, particularly rocket launching on Northern Israel seems more realistic. Nasrallah previously said that he would fore sure respond. The real question is how and where will he respond, because now Hezbollah has the possibility to strike Israel from two different locations: From South Lebanon, where most of its rocket Arsenal is based , and from Syrian Golan Heights , were he can strikes virtually any Israeli Targets, since the rocket-defense (Iron-Dome battery) of Israel on this region is weaker than on the Lebanese border.

Old strategies are no longer yielding results for Venezuela. Nevertheless, in 2016, the Venezuelan government will continue prioritizing foreign debt payments and reinvestment into the energy sector at the expense of imports. So far, this strategy has allowed it to maintain oil production and avoid a disorderly default on its foreign debt. But challenges will arise as inflation frustrates voters and public funds become depleted.

To make matters worse, the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela’s (PSUV’s) potential loss of its legislative majority in Dec. 6 elections could diminish the government’s firm control over the legislative branch. Moreover, renewed protests by the opposition in 2016 are likely to be more threatening than the wave of unrest that occurred in 2014, simply because the economy is in much worse condition. As the economy deteriorates and unrest mounts, the government’s unity will be tested, and deeper splits could develop between the major political factions running the country.

Analysis

In the coming year, the Venezuelan government will continue relying on a strategy it has long used to avoid deeper economic turmoil. Since 2013, Venezuela’s central government, which has a near monopoly on the legal disbursement of foreign currency in the country, has cut imports in an attempt to safeguard its dwindling stock of dollars. (In 2015, Venezuela slashed imports by about 25 percent from the year before.) Its goal is to maintain access to its limited foreign lenders at all costs, even though its strategy will spur inflation and exacerbate shortages of food and consumer goods.

This approach is unsustainable in the long run. Venezuela’s high levels of public spending, combined with declining investments into the energy sector, the loss of foreign lending and severe economic distortions that encourage the arbitrage of currency and Venezuelan-produced fuel, have all sapped the country’s public finances. These problems have only worsened since global oil prices began declining in 2014. Consequently, economic reform is politically unpalatable in Venezuela at the moment. Instead, the government has chosen to hope for the best and wait for oil prices to creep back up while it settles on a method of dealing with impending unrest and potential financial default.

Two events could challenge the government’s wait-and-see approach to managing Venezuela’s considerable economic difficulties. The first is the Dec. 6 legislative elections. If the opposition wins by a significant margin, it could gain enough political power to weaken the PSUV’s unchallenged 15-year hold over the three branches of government. The second is the possibility of renewed political unrest from sections of the political opposition or even from disgruntled former supporters of the ruling party. With inflation in 2015 likely to exceed 200 percent compared with the previous year, a significant portion of the population is feeling the effects of rapid price increases and food scarcity. Although protests related to inflation have been limited in size and impact, inflation is set to increase in 2016 and could eventually lead to more frequent and sizable demonstrations largely from the urban and rural poor, the ruling party’s largest support base.

The election poses the most immediate threat to the ruling party. If the opposition wins the election by a wide margin, it could wield considerable influence. A three-fifths majority (101 of the 167 legislative seats) would give the opposition the power to remove the vice president and Cabinet ministers. A supermajority of 112 legislators would allow the opposition to designate members of the crucial National Electoral Council, Venezuela’s highest electoral body. It would also potentially empower the opposition to call for a Constitutional Assembly, which can be used to heavily modify the constitution. In the worst-case scenario, the legislative vote poses an existential threat to Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro’s government, albeit one that it cannot simply cancel for fear of giving opposition forces a rallying point for protests.

But barring a supermajority for the opposition, the Venezuelan government has some measures it can rely on to keep the opposition in the legislature in check. It can still use the presidential veto or the Supreme Court’s constitutional chamber to overturn legislative decisions. Using these bodies, in combination with selective concessions to the multiple factions within the opposition coalition, Maduro could create enough disruptions to limit the influence of an opposition-led National Assembly. Such an outcome would lead to greater political conflict between segments of the opposition and the government amid a deepening economic crisis that the government can do little to address.

Renewed opposition-led protests in 2016 will also threaten the government. In 2015, the promise that a legislative victory was within the opposition’s grasp likely kept coordinated protests against the state in check. But next year, there will be no such limitations, and sections of the opposition such as the Voluntad Popular party and student organizations could ramp up their demonstrations against the government. With inflation and shortages far worse than those seen during the wave of protests that swept the country in 2014, renewed demonstrations pose a real risk to the government. The demands of any demonstrations could include Maduro’s resignation; starting next year, Maduro can be legally recalled via referendum. If the unrest becomes severe enough, it could also force splits among the factions of the PSUV as members of the party’s elite seek to safeguard their stakes in the national political system.

Meanwhile, the lack of an economic cushion for public finances will keep the risk of financial default alive next year. Meeting foreign debt payments has been an essential part of the ruling party’s strategy to maintain access to Venezuela’s limited foreign lending. During Maduro’s tenure, the government began reducing imports to keep meeting those payments and lower the government’s overall spending. But the PSUV and the government are in a difficult spot. About $16 billion in foreign debt payments is due in 2016, including interest payments. The government has already eaten through $7.2 billion in foreign reserves (32 percent of its total reserves) this year, and off-budget funds that previously bolstered additional spending, such as the National Development Fund, are likely heavily drawn down because of the reduced availability of dollars from oil exports. With few additional sources of revenue outside of state-owned Petroleos de Venezuela’s income, default in the coming year is plausible. At this point, Caracas’ likely options are to delay default by conducting a voluntary Petroleos de Venezuela bond swap or to sell its increasingly limited assets, although the success of such measures is highly dependent on investors’ and bondholders’ perceptions of the country.

Forecast

- Even as tensions in the Pacific Rim increase, military ties between China and the United States will become tighter.

- China will continue to cooperate with the United States and Japan to establish mechanisms to manage crisis situations.

- U.S. arms sales to Taiwan near the start of 2016 will not lead China to suspend military relations with the United States.

Analysis

After reaching their apex in the final decade of the Cold War, military-to-military ties between China and the United States entered a two-decade tailspin. In the interlude, China emerged as a major power in the Pacific Rim. Now, with Beijing’s regional heft at an all-time high, regional military tensions are elevated, especially in the disputed waters of the South China Sea. In this volatile environment, the United States and China are now looking to military relations as a tool for developing strategic trust, making accidents less likely and helping to manage them when they inevitably occur.

Since 2011, and especially since Xi Jinping assumed the presidency in China, the two sides have worked to rebuild their relationship. This process is now speeding up. On Nov. 19, the People’s Liberation Army hosted a U.S. Army delegation in Beijing for the first meeting of the U.S.-China Army-to-Army Dialogue. The initiative was signed between the defense establishments in June and includes a raft of confidence-building measures. It is part of a trend that will continue even as military tensions grow in the Pacific Rim.

Highs and Lows

Military relations between China and the United States were at their height in the final decade of the Cold War. The foundation of the relationship was a shared interest in countering the power of the Soviet Union, Beijing’s regional rival and Washington’s global competitor. When Deng Xiaoping assumed power in 1979, Washington and Beijing formed an entente to counter Moscow. At the height of these relations, the United States sold military equipment to China and even agreed to transfer military technology to the People’s Liberation Army, a move that would be unthinkable today. These technology transfers included a modern ammunition production line and an avionics upgrade for Chinese J-8 fighters. China reciprocated by allowing the United States to operate a listening post in the northwestern province of Xinjiang to collect data on Soviet nuclear tests.

This cordial relationship broke down suddenly when the Chinese military cracked down on protesters during the 1989 Tiananmen Square Incident, but its real decline was due to the crumbling of the Soviet Union. In response to Tiananmen, the administration of U.S. President George H.W. Bush cut military ties with China, suspended technology transfers and imposed sanctions that prohibited U.S. arms sales. These restrictions are still in place. But Beijing’s crackdown on protesters was merely the catalyst. At the height of Sino-Soviet tensions, China’s military had stared down more than 30 Soviet armored divisions to the north, as well as the threat of battle-hardened and Soviet-aligned Vietnam to the south. By 1989, however, the Soviet Union was already beginning to fall apart, bringing an end to the mutual threat that had united Washington and Beijing. As Soviet power collapsed, most of its forces on the border were withdrawn. With the former Soviet space in disarray, China no longer had to devote its resources to this long land border. Freed up from this obligation, China turned its attention to maritime disputes in the East and South China seas. The People’s Liberation Army has also returned its focus to reunification with Taiwan, the most acute point of tension with the United States.

Though the end of the anti-Soviet entente made a decline in military ties inevitable, the degree to which they deteriorated was remarkable under the presidencies of both Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. Efforts to mend the relationship began in 1993 with the resumption of military-to-military ties, but crises frequently disrupted progress, particularly the collision of a U.S. surveillance plane and Chinese fighter in April 2001 over the South China Sea. This collision, known as the Hainan Island incident, led the United States to once again suspend relations. Compared to the 1980s, China also became far more willing to cut ties to make a political point, frequently canceling planned visits and formal communications between the People’s Liberation Army and U.S. military. These disruptions became Beijing’s default response to major U.S. arms sales to Taiwan.

Beijing and Washington put in place several communications mechanisms during this period, including the Defense Telephone Link in 2007; these often went unused. Senior U.S. officials involved in the many Sino-American crises during this time recalled frustration with China’s seeming unwillingness to answer phone calls. Unstable relations and unreliable communications made conflict resolution difficult at a time when increasing Chinese force projection capabilities made clashes between China and its neighbors more likely.

A New High

In recent years, the military-to-military relationship has begun to stabilize once again. Although it is by no means back to pre-1989 levels, neither country has canceled major military interactions since 2011. This improvement roughly corresponds with the start of Xi Jinping’s tenure as vice chairman of China’s Central Military Commission, the military’s core leadership body, in October 2010. He later became chairman in November 2012. This was an early indication of his interest in strengthening military-to-military relations during his presidency, which began in March 2013.

Under Xi, the People’s Liberation Army has increased the frequency of joint drills with the U.S. military, culminating in the United States inviting the Chinese navy to participate in RIMPAC 2014, the world’s largest multilateral naval exercise. This was a symbolic milestone. The People’s Liberation Army also built up its regularized communication mechanisms with the U.S. military, including the army-to-army dialogue that kicked off in November. More critically, the Chinese military made a serious effort to establish and implement crisis management mechanisms. At the 2014 Western Pacific Naval Symposium, the People’s Liberation Army Navy agreed to abide by the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea, which establishes common protocols for interactions between naval vessels to reduce accidents. In September, China signed a bilateral agreement with the United States governing air-to-air encounters as well as protocols governing the use of the Defense Telephone Link. The two navies are also set to hammer out a set of rules on ship-to-ship encounters in the near future.

What is most notable about these newly stabilized military-to-military ties is that they come during a period of tumult between China and the United States as well as China’s neighbors. Under Xi, Chinese incursions in the Japanese-controlled Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands have increased. China also declared an Air Defense Identification Zone over the East China Sea while accelerating land reclamation in the South China Sea. This is partly due to the fact that the People’s Liberation Army itself appears to have shifted its attitudes and now believes that military-to-military ties with the United States can bring it tangible benefits. At the same time, China’s top political leadership now recognizes the need for more tools to manage disputes.

Above all, however, these changes are symptomatic of China growing into its role as a great power in all respects, including how it handles military relations. Like the Soviet Union, China is discovering that great powers need ways to manage crises with their potential military opponents — something uniquely important given China’s increasingly global interests. There are diminishing returns to politicizing the U.S.-China military relationship. To do so would both raise the risk of a military crisis with the United States and make it politically easier to isolate China from regional security arrangements. This is doubly critical as Japan makes strides in military normalization that further complicate China’s periphery.

China’s commitment to stable military ties with the United States will be tested very soon. The first major Taiwan arms sale since 2011 is coming up, likely in December 2015 or January 2016. This will be especially important to watch given China’s stock response to such deals under the previous two administrations: suspending U.S. military-to-military ties. The latest source information, however, indicates that China will likely only make pro forma responses of displeasure and not suspend ties. The Chinese leadership now highly values military-to-military ties and has made obtaining an invitation to RIMPAC 2016 a political priority. Although the bilateral military relationship will likely not return to the highs of the 1980s, it will remain much more robust and stable than that of the period between Tiananmen and the end of Hu Jintao’s presidency.

July 21st Burundi General elections

In this elections, the Burundi government held a surprise to all. Burundi’s president, Pierre Nkurunziza, was sworn in for a third term six days ahead of schedule, without giving explanation for such a move.

Burundi’s president, Pierre Nkurunziza, has won a predictable victory in a disputed election surrounded by violence and an opposition boycott. He is set to serve a third five-year term after taking 69.41% of the vote, 50 percentage points ahead of his leading opponent, Agatho n Rwasa.

In his inauguration speech, Nkurunziza already made plenty of promises that he expects to fulfill in his additional term in office. President has pledged to end months of violence in Burundi and called on those who fled the country to return. In his oath, the president swore loyalty to the constitution, to assure national unity and the cohesion of the people. He also promised to bring stability following months of violence that claimed the lives of at least 100 people and prompted more than 167,000 to flee the country. However, experts analyze the impact of these statements on the Burundian society, and it appears that many Burundians think this president should not be president at all. Nkurunziza is generally not an accepted leader within his own people.

Burundi has seen a wave of persistent protests against him seeking a third term. Nkuruniza’s plan to seek a third term in office was deemed unconstitutional by the opposition. Three of Nkurunziza’s seven opposition candidates formally boycotted the vote, while Rwasa said he would not recognise the result. It is believed, howev

er, that the government will now face plenty of difficulties to calm the youngsters anger and to satisfy their demands. Denial for this new election has come as well from the opposition parties, who have said they will not recognize a Nkurunziza presidency.

From the international perspective, there is a pressure applied by Western government on Burundi’s President for opening a dialogue with his opponents. Additionally, they have condemned the election as not credible due to the harassment and intimidation of the opposition, rights activists, journalists and voters. This critiques have been perceived quite ineffective, to the point that it is feared that Nkurunziza would seek international support else wise, by turning away towards countrie

From the international perspective, there is a pressure applied by Western government on Burundi’s President for opening a dialogue with his opponents. Additionally, they have condemned the election as not credible due to the harassment and intimidation of the opposition, rights activists, journalists and voters. This critiques have been perceived quite ineffective, to the point that it is feared that Nkurunziza would seek international support else wise, by turning away towards countrie

s like Russia or China.

This overall political crisis is believed to be able to trigger social repercussions, such as an internal division within the army in the country. It looks like these critical elections for the country have again failed to create an optimal political and social situation for Burundi.

Analysis

During a bilateral summit held Nov. 29, the European Union and Turkey agreed on several measures to reduce the number of asylum seekers arriving in Europe. Though the deal represents the first comprehensive plan to address the migration crisis in Europe, it is constrained by the conflicting political interests of the negotiating governments.

According to the agreement, the European Union will provide Turkey with 3 billion euros (roughly $3.2 billion) to help Ankara deal with refugees in its territory. However, the money will be disbursed in tranches, which depend on Turkey’s commitment to and success at improving border controls, fighting human trafficking organizations and offering working rights to refugees in the country. Like the bloc’s approach to bailouts for countries in the eurozone, the mechanism will probably create a cycle of assessments and negotiations over whether or not Turkey is holding up its end of the bargain, giving European leaders plenty of chances to stall on important decisions. The European Union also has to decide where the money will come from. The EU Commission has suggested it will contribute some 500 million euros, and Germany and France can be expected to contribute. But it will be up to the member states to come up with the rest and to decide who will provide what — another likely point of contention.

The agreement also comes with potential political benefits. European leaders have promised to hold bilateral summits with Turkey twice a year and, perhaps more important, restart Turkey’s EU accession process by opening negotiations over monetary policy. It is one of the few accession chapters to which the island of Cyprus has not presented a veto. The Cypriot government has long opposed Turkish accession without substantial progress in the negotiations over reunifying the island, which is divided between a Greek Cypriot republic in the south and a Turkish Cypriot government in the north. Brussels simply found a creative way around the obstruction.

Finally, the European Union offered to “accelerate” the process to lift visa restrictions for Turkish citizens visiting the Schengen area. Like the disbursement of the money, this will also be linked to Turkey’s progress on implementing border measures and constant assessments. Brussels is now expected to present a report in March, followed by a second report later in the year, with the goal of completely lifting visa requirements by October 2016. It is still unclear whether the EU members that are reluctant to give 75 million Turks visa-free access to Europe will change their minds in the next 10 months, especially as European countries continue to restrict rather than facilitate the movement of people.

The Debates Continue

While EU leaders conceded as much as they could to Turkey, the agreement will not put an end to the bloc’s political disputes. Domestic political considerations are driving the German government to do more to reduce the arrival of asylum seekers. Conservative forces are demanding that Chancellor Angela Merkel impose a quota of migrants entering Germany. Merkel, conversely, is calling for an EU-wide quota linked to a voluntary distribution of asylum seekers across the Continent. Similar plans to redistribute asylum seekers currently residing in Greece and Italy have so far failed, and after the terrorist attacks in Paris several EU members said they would no longer accept the share of immigrants that they had previously agreed to.

Meanwhile, nationalist parties — in Germany but also across Europe — continue to benefit from popular discontent over the migration crisis. According to a poll for German paper Bild am Sonntag, roughly half of Germans want Merkel to resign, while popularity for the anti-immigration Alternative for Germany party is at roughly 10 percent, a record high. In France, opinion polls show that the nationalist National Front party could win the election, the first round of which will take place Dec. 6, in as many as three of France’s 13 regions. That level of success would be a milestone for the party, which is currently popular but only controls a handful of small municipalities in France.

Ultimately, even if Turkey and Europe meet all the requirements of the agreement, and if the European Union finally succeeds in implementing some redistribution mechanism for asylum seekers,it will not solve the crisis completely. While improved border controls in Europe and Turkey and more coordination in the fight against human trafficking organizations could somewhat reduce the movement of people between the Middle East and Europe, the conflict in Syria will linger, driving Syrians from their homes in search of safer locales. The conflict will continue to shape political developments in Europe and to challenge the continuity of the European Union as it exists today.

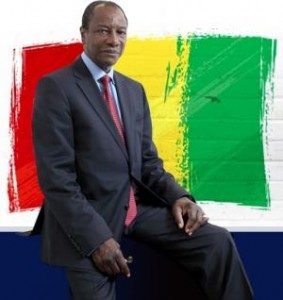

October 11th Guinea Presidential elections

Guinea’s President Alpha Conde has won re-election and will serve a second five-year term, gaining nearly 58 percent of the vote, compared to opposition leader Cellou Dalein Diallo, who won a tick over 31 percent. As an immediate reaction Diallo said he did not recognise the final result and would call on his supporters to protest against fraud and vote rigging. Diallo accused the commission and the government of abuses including ballot stuffing, allowing minors to vote, changing the electoral map and intimidation. But he said he would not appeal to the court.

Guinea’s President Alpha Conde has won re-election and will serve a second five-year term, gaining nearly 58 percent of the vote, compared to opposition leader Cellou Dalein Diallo, who won a tick over 31 percent. As an immediate reaction Diallo said he did not recognise the final result and would call on his supporters to protest against fraud and vote rigging. Diallo accused the commission and the government of abuses including ballot stuffing, allowing minors to vote, changing the electoral map and intimidation. But he said he would not appeal to the court.

In a country with a history of political violence, several people were killed in election-related clashes. But the margin of Conde’s victory may make it harder for Diallo’s accusations to gain traction.

Conde took power in 2010, ending two years of military rule during which security forces massacred more than 150 people at a stadium in the capital. Guinea has experienced two authoritarian rules since its independence from France in 1958.

This election has handed in to Conde another chance to revive the West African nation’s economy, which has been pummeled by a lingering Ebola outbreak and a drop in metals prices. According to the Human Rights Watch, the government of President Alpha Condé had made progress in addressing the serious governance and human rights problems that characterized Guinea for more than five decades. However, gains in promoting the rule of law and development could be reversed by the 2015 presidential elections, a major trigger for unrest and state-sponsored abuse; lingering ethnic tension.

The history of elections in Guinea amounts to the successful completion in 2013 of parliamentary elections, which advanced Guinea’s transition from authoritarian to democratic rule, mitigated the concentration of power in the executive branch, and led to a drastic reduction in violent political unrest and state-sponsored abuses. However, local elections scheduled for 2014 failed to take place, which periodically stoked political tensions. There were also regular protests over electricity cuts, as well as several lethal incidents of communal violence.

On a different perspective, the government of Guinea made some progress in ensuring accountability for past atrocities, including the 2009 massacre of unarmed demonstrators by security forces. However, inadequate progress on strengthening the judiciary and endemic corruption continued to undermine respect for the rule of law and directly led to violations. International actors have quite failed to denounce this situation in the country and to assist the government in these issues.

May 24th Ethiopia General elections

Although it is formally described as a multi-party system, the crushing victory of the Ethiopian dominant party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), has put at stake the electoral procedure and the party system in the country. The EPRDF has been ruling the second most populated country in Africa for over two decades and seems to stay in power for an even longer period now. Indeed, the political landscape drawn this time goes as follows: opposition party will not hold a single one in the parliament elected, and of the 1,987 seats in the regional parliaments, it will have only reached 21 of seats.

As stated by the chairman of the electoral board, “the general elections were characterised by high voter turnout and orderly conduct of the elections proceedings. The elections were culminated in a free, fair, peaceful, credible and democratic manner”.

One main explanation for the continuing of the ruling party has been the economic progress made by the country ever since the EPRDF took control of the government. In fact, Ethiopia, whose 1984 famine triggered a major global fundraising effort, has experienced near double-digit economic growth and huge infrastructure investment, making the country one of Africa’s top-performing economies and a magnet for foreign investment. Ethiopia also remains a favourite of key international donors, despite concerns over human rights, as a pillar of stability in an otherwise troubled region.

The main problem of the electoral process by far has been that, as accusations have been made by rights groups, Ethiopia constantly clamps down on opposition supporters and journalists, and of using anti-terrorism laws to silence dissent and jail critics.

African Union observers said the polls passed off without incident, but the opposition alleged the government had used authoritarian tactics to guarantee victory. Activists have said the polls were not free or fair due to a lack of freedom of speech.

The United States, which enjoys close security cooperation with Ethiopia, said it remained “deeply concerned by continued restrictions on civil society, media, opposition parties, and independent voices and views”. On its part, the EU has also said that true democracy had yet to take root in Ethiopia.