By the former US Ambassador David H. Shinn. The Indian Ocean occupies about 14 percent of the earth’s surface and nearly 50 percent of world trade transits these waters. Since the beginning of this century, much attention has been given to the Indian Ocean because of piracy from the Gulf of Aden to the Strait of Malacca, growing Chinese naval activity in the region, the occasional natural disaster such as the 2004 tsunami, and the 2014 loss of Malaysia Airlines flight 370. One important Indian Ocean issue that has received little discussion is the potential impact of deep seabed mining.

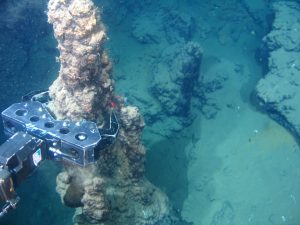

There are three types of deep seabed mineral deposits. The most accessible deposits are seafloor massive sulfides (SMS) found in water from 1,500 to 2,500 meters deep. These deposits typically contain high amounts of copper, zinc, gold, and silver. The second category is polymetallic nodules located on the ocean floor between 3,000 and 4,000 meters deep. They are mineral clumps with varying amounts of manganese, cobalt, nickel, and copper. Cobalt-rich crusts are the third category of seabed mineral deposits and found at a depth of 700 to 2,500 meters. They contain cobalt, nickel, tellurium, and rare earth metals.

Credit : RSC Geological Consultants

Mining of these minerals is complicated and expensive; it also raises a host of geopolitical and environmental issues. Consequently, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) was established in 1994 under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). As of mid-2016, 168 nations were members of the ISA, which has its headquarters in Jamaica. The United States is the only major maritime country that is not a member because it has not ratified UNCLOS, arguing it could impinge on its sovereignty. The ISA mandate is to organize, regulate, and control all mineral-related activities in that part of the international seabed outside the exclusive economic zones of individual countries. UNCLOS defines this area as “common heritage of mankind” that is not subject to direct claims by sovereign states.

Only a small number of entities has the capability to pursue deep seabed mining. Most of the contractors are governments such as South Korea, Russia, and India or companies sponsored and funded directly or indirectly by governments through public funding such as the China Ocean Mineral Resources and Development Association housed in the State Oceanic Administration and the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources. China, India, Japan, South Korea, Germany, and Russia are all seeking deep seabed minerals for their own use.

Most deep seabed mining areas are in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, but the Indian Ocean has also designated areas for exploring for SMS and polymetallic nodules. The government of India holds the only ISA contract so far to explore for polymetallic nodules in the Indian Ocean. In the case of SMS, the ISA has agreed to four contracts with the governments of India and South Korea, the China Ocean Mineral Resources and Development Association (COMRA), and the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources.

The two countries most engaged in exploring for deep water seabed minerals in the Indian Ocean are India and China. Their immediate goal is to identify where the minerals are located. India’s research vessel, RV Sindhu Sadhana, began by exploring for polymetallic nodules in the Mid-Indian Basin. It added exploration for SMS to its efforts in the Southern Indian Ocean in a zone stretching close to the Mauritius coastline. India’s goal is to develop a stockpile of rare earths as a direct response to China’s dominance and control over production and marketing of these strategic metals.

Credit: National Institute Of Oceanography( NIO ) –

China has been the most active country in the Indian Ocean where it has been exploring for SMS along the Southwest Indian Ridge in a 10,000 square kilometer area just south of Madagascar. As the world’s largest importer of metals, 46 percent of the global total in 2014, deep seabed mining is a critical issue for China. Its first manned deep submersible, the Jiaolong, has made several research visits to the Indian Ocean. China also has an unmanned submersible, the Qianlong. Tao Chunhui, a researcher at the State Oceanic Administration, commented last year that “China has made huge progress in deep-sea technology.”

In 2015, the deputy director of China’s State Oceanic Administration, Chen Lianzeng, visited India and suggested the two countries enhance cooperation on oceanic research and development, adding they could share the costs, risks and benefits. Beijing’s overture immediately followed the completion of the 118-day research trip of the Jiaolong to the Southwest Indian Ocean. The deputy director of COMRA, He Zongyu, added that India and China face similar challenges and COMRA is willing to cooperate with India in every way. There is no indication that India has responded positively to this initiative.

In addition to the geopolitical implications of deep seabed mining in the Indian Ocean, there are significant environmental concerns. Richard Steiner with Oasis Earth points out that given the “poor understanding of deep sea ecosystems, growing industrial interest, rudimentary management, and insufficient protected area, the risk of irreversible environmental damage here is real.” He argues that before deep sea mining advances, it requires much more extensive scientific research on species identification, community ecology, distribution, genetics, life histories, resettlement patterns, and resilience to disturbance. There is a little time to improve knowledge about the environmental concerns as mining on the international deep seabed is probably five to ten years off.

About David Shinn

David has been teaching in the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University since 2001. He served previously in the U.S. Foreign Service for 37 years including as ambassador to Burkina Faso and Ethiopia.