The next phase of Myanmar’s political transition has been settled. China is monitoring closely the elections. The results of the country’s Nov. 8 elections have confirmed that the opposition National League for Democracy now holds a healthy majority in parliament and can form a new government without the help of the formerly ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party. For the first time since Myanmar’s 1962 coup, a fully civilian party will lead the government, although it will still have to vie for power with the country’s military elite.

Meanwhile, China has been watching Myanmar’s political transition with growing concern. Myanmar, which shares a 2,192-kilometer (1,362-mile) border with China that cuts across rugged highlands, represents access to trade routes in the Indian Ocean Basin and to overland commerce with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), now China’s largest trading partner. However, the relationship between the National League for Democracy and Chinese leaders has been cool; Beijing conspicuously avoided congratulating party chief Aung San Suu Kyi on her victory. This track record would seem to suggest that she will lead her party — and her country — toward the West, in both diplomatic and economic terms. But Suu Kyi’s actions and tactics will still be informed by Myanmar’s geopolitical position, and regardless of the party in power in Naypyidaw, China will continue to play a massive role in the Myanmar capital.

The Road Away From China

Myanmar’s latest round of elections was the culmination of 12 years of planning by the country’s political elite, who laid out a roadmap in 2003 for Myanmar’s transition to quasi-civilian rule. The gradual, strategic loosening of the military’s grip is a reaction to the failed attempt to open up Myanmar’s economy in the early 1990s, which left the country wholly dependent on economic and political support from China. This position was geopolitically untenable for Myanmar, which desperately needed to integrate into the international community.

Since 1962, Myanmar had systematically cut itself off, both economically and politically, from the fraught Cold War environment in Southeast Asia. The country also faced ethnic and communist insurgencies, some of which received direct support from Beijing.

Once the Cold War was over, Myanmar tried to turn outward once again, in spite of its need to maintain tight control at home amid the ongoing unrest. But when the military government nullified the country’s elections in 1990, the West imposed economic sanctions, forcing it to turn to China for survival. Between 1988 and 2013, 42 percent of Myanmar’s total foreign investment (some $33.67 billion) and 60 percent of its arms imports came from China. By the early 2000s, some of Myanmar’s leaders began to worry that they had become too reliant on China and began searching for a solution. They eventually settled on a roadmap to democracy that would gradually open Myanmar’s political system to opposition parties — primarily the National League for Democracy — to please the West and give Naypyidaw the opportunity to seek partners other than China.

A Government Divided

The National League for Democracy’s Nov. 8 victory was the logical conclusion of this process and one for which Myanmar’s military elite have long been planning. They erected a constitutional hedge around the military’s position and assets, securing 25 percent of the seats in parliament, consolidating control of several key ministries and economic enterprises, and ensuring that retired soldiers will be incorporated into the bureaucracy. Consequently, the new government will need to strike an accord with the military if it hopes to transition into power smoothly.

Beijing has also been planning for the transition. In June, China invited Suu Kyi to meet with Prime Minister Li Keqiang and President Xi Jinping in Beijing. It also made a point to reach out to other parties, meeting with the Union Solidarity and Development Party in April and, in an unprecedented move, the powerful ethnic minority Arakan National Party in July.

After the vote, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was quick to issue its congratulations for the orderly conduct of elections and to express hope for long-term stability and growth. However, it omitted any reference to the National League for Democracy, in part because the elections’ outcome has complicated the power structure in Naypyidaw. Now the National League for Democracy will control the parliament while the military controls the state’s more permanent structures, including the key ministries, economic assets and, of course, hard power. At the same time, ethnic parties that won at the state level but not in the national elections may cause trouble as they jockey for position.China will now have to deal with the multiple power brokers contributing to Myanmar’s policy decisions.

Choosing how to deal with ethnic minority insurgents will be a key point of contention in Myanmar moving forward. For over half a century, the military has fought to regain territory from and weaken these groups. Now the insurgents are demanding political concessions in exchange for peace. Beijing, which has long supported the groups on its border (especially the United Wa State Army and the Kachin Independence Army), has leveraged its influence over them in the past to check Myanmar’s attempts to move away from China. Indeed, the groups’ decision not to sign an Oct. 15 cease-fire deal with Naypyidaw was allegedly made at Beijing’s request. As China continues to bolster Myanmar’s insurgencies, the National League for Democracy will try to make political compromises with Beijing, but it will have to contend with a military that wants to continue eroding the ethnic groups’ position.

Finding New Trade Partners

Much has been made of Myanmar’s supposed pivot away from China, and the country has certainly managed to diversify its sources of foreign investment since its 2010 transition. But Myanmar’s geography limits how far it can stray from China. China’s Yunnan province, though poor by Chinese standards, is quite dynamic compared with the four remote Indian states to Myanmar’s west or Bangladesh to the southwest. In a bid to develop its interior, China wants to build outlets for the landlocked Yunnan — outlets that would run through Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar. As a result, though Myanmar will seek to balance its neighbor to the east, China will continue to be an essential trading partner.

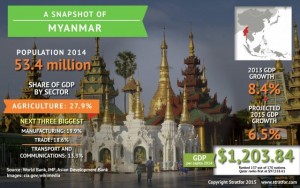

Much has also been made of the decline of the Chinese economy since 2010, but China still plays the most important role in Myanmar’s economy and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. It is simply too big and too near to expect otherwise. In 2014, China accounted for 42.7 percent of Myanmar’s imports by value and 65.2 percent of its exports. Myanmar’s next-largest partner, Thailand, is dwarfed by comparison, accounting for 19.3 percent of Myanmar’s imports by value and 16.4 percent of its exports. And the official statistics do not account for the massive outflow of narcotics, black market timber, and minerals or gems that also bring Chinese money into Myanmar. In the face of this reality, the West could only play the role of a spoiler at best, possibly cutting trade deals and providing diplomatic and technical assistance to Myanmar in the hope of strengthening ties. But even that will have its limits; the United States is much more concerned with the balance of power in the South China Sea than it is with a newly open Myanmar.

But what is different this year is that Myanmar has broadened its sources of economic support. The Asia Highway connecting Thailand and India via Myanmar was completed in 2015. This will tie Myanmar to the more dynamic Thai economy. Myanmar and Thailand also laid the policy groundwork for a special economic zone between the Thai border town of Mae Sot and Myanmar’s Myawaddy, which have had limited formal border connectivity in the past. This huge step will be further enhanced by connections to a planned deep sea port in Dawei, Myanmar. As Thailand tries to move up the economic value chain, it will shed some production that will fall to Myanmar, in turn moving Myanmar’s economy away from primary resource extraction.

Meanwhile, the West’s much-touted entrance into Myanmar has remained comparatively limited. Trade with the United States and Europe is still anemic: Exports to the United States accounted for only 0.4 percent of Myanmar’s trade, and imports did not fare much better. Europe has fully repealed its sanctions against the government. The United States lifted its investment ban in July 2012, but it still has targeted sanctions in place on key industries and business leaders. Suu Kyi, as part of an attempt to forge ties with Myanmar’s military-backed elite, may try to use her Nobel laureate status to push for an end to these sanctions and possibly for favorable trade deals. For now, though, sanctions have a huge impact on trade; for example, a sanctions issue squeezed U.S.-Myanmar shipments from $50 million in June to $5.5 million in September. The only sector that has benefited from greater Western involvement is energy. In March, Chevron’s Unocal Myanmar Offshore Co. signed a $277 million contract for one block and BG Group and partner Woodside Petroleum together signed a $1 billion deal to explore four offshore blocks. These deals will provide much-needed cash for the Myanmar government, which suffers from limited tax income because of its weak institutions.

For the most part, China boasts more options in Myanmar — and Southeast Asia as a whole — than it had in 2010. Beijing has managed to complete a pipeline connection running through Myanmar to the Bay of Bengal, a project that is one small component of China’s broader strategy to diversify its energy inputs and pump directly to its poorly developed interior. However, the accompanying highway project has yet to materialize, and a major hydropower project, the Myitsone Dam, is on hiatus through the end of the year. Still, China has plans to send connections into Thailand through Laos and Vietnam. Myanmar is one option for China’s energy schemes, but it is not the only one.

Beijing can afford to play the long game in Myanmar. It can even afford to lose out entirely on any future business so long as it can retain its current projects. Whatever potential reorientation Myanmar’s new government may bring, China will leverage its significant influence in the country to seek an advantage over the West, while the West will use Myanmar in a limited way to balance against China in the Asia-Pacific.