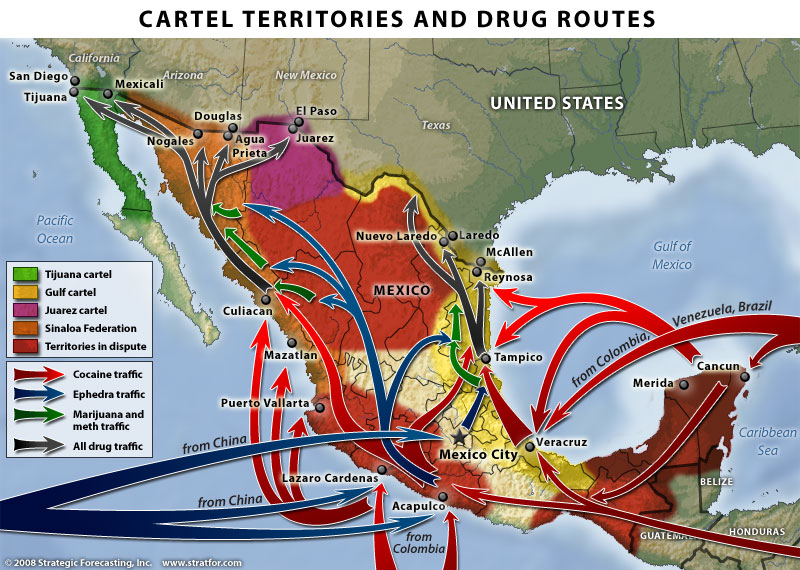

Mexico has endured a ragging war against drug cartels ever since former President Felipe Calderon declared the War on Drugs back in 2006[1]. From then on, violence exploded[2], cartels grew, and others came to be as the government couldn’t effectively stop them from spreading.

“Sexenio” after “sexenio” (the name given to the six-year period that a President remains in office in Mexico), the different ruling governments have been increasingly criticized[3] by the population due to the unceasing increase in violence[4]. This (among other factors that relate to corruption and social inequality) has caused the approval ratings of every presidency to plumber. In fact, according to Consulta Mitofsky (Mistofsky Consulting)[5] and Parametría the popularity of former President Enrique Peña Nieto fell from 53% approval at the beginning of his mandate in 2012 to 18%-28%[6] by the end of his presidency in 2018.

Admittedly, the War on Drugs has been largely considered a “failed war”[7]. The reason being that ever since it started, it had no effect on drug trafficking, on the contrary, Criminal activities such as kidnapping, extortion, and murder increased. In fact, “as of November 2012, an estimate 57,400” murders[8] were “drug-related violence since Calderon deployed the military in 2006”[9]. Today (2020), that number rises above 250,000[10] criminal activity-related homicides. Proportionally, the number of troops deployed by the government grew from approximately 45,000 troops[11] during Calderon’s administration to 100,000 “strong-force”[12] elements of the National Guard[13] by 2020.

This gradual increase of troops can be explained by the high level of weapon availability[14] to drug cartels. As shown by Christopher, Colin, and Chad[15]: “better-armed adversaries require better-armed police and military forces, and such a scenario will increase law-enforcement and military casualties, regardless”. Notably, high-level weapon availability is linked to the gun-related policy of the US. As a matter of fact, 70%[16] of the weapons used by the cartels in Mexico are produced or come from the US, these figures have been consistent for many years according to Bradley Engelbert[17], spokesperson for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives of the US. Portraying thus, the inefficiency of the measures taken by both the Mexican and the American governments to contain weapons smuggling. In fact, according to the new Estrategia de Seguridad Pública del Gobierno de la República (Public Security Strategy of the Government of the Republic) ESPGR, there are around 200,000[18] weapons smuggled into the country every year (other specialists place this figure as high as 250,000)[19]. While estimates show that only 3% of the population owns a weapon, 72% of the people assassinated in Mexico are killed by firearms.

In this regard, Presidents Felipe Calderon and George W. Bush signed the Mérida Initiative in 2007[20]. This document was an agreement of both governments to allocate more resources, namely in technology, and foster cooperation in counternarcotic and law enforcement agencies to the military and security forces of Mexico to combat opioids trafficking and weapons smuggling[21]. This traditional approach against drug trafficking raised many questions as it emphasized a coercive action[22] and ended up showing ineffective. As a matter of fact, Eric Olson says: “public commitments by U.S. officials to disrupt firearms trafficking (…) in the United States were not tied to specific targets or funding initiatives. As a result, there were doubts about how serious the United States was at addressing its own responsibilities in the struggle against criminal groups”[23]. Whereas in it’s the first phase, the Mérida Initiative was focused on better training and equipping Mexican forces to trump the capabilities of drug cartels, during the Obama administration this approach shifted “toward addressing the weak government institutions and societal problems that have allowed the drug trade to thrive”[24].

With the introduction of the 4 pillar approach to the Mérida Initiative, President Obama refocused (1) on disrupting and dismantling Criminal Organizations, (2) institutionalizing the rule of law, (3) building a 21st-century border, and (4) building strong and resilient communities[25].

However, by 2016 the US Congress had drastically reduced its funding to Mexico and refocused on expanding its agenda by relocating financial aid to the Central American States. Meanwhile in Mexico, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) readjusted respectively 61% and 54% of the funding provided to Mexico in the 2nd pillar of the Mérida Initiative. As the Peña Nieto administration came into office, the new security strategy redirected the channels of collaboration from decentralized to centralized; the Secretaría de Gobernación (Secretariat of the Interior) became the sole channel by which projects of cooperation between the American and Mexican authorities ought to be approved. Peña Nieto also encouraged the creation of the Bilateral Security Cooperation Group (BSCG) to further expand collaboration at the highest levels. Aside from this, Peña Nieto’s approach to the Mérida Initiative didn’t change much from Calderon’s s[26].

By 2019, the new administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (better known as AMLO), faced the hard public stance of President Donald Trump on borderline security[27]. In exchange for avoiding trade tariffs, AMLO recruited and deployed 15,000 elements of the National Guard to the North of Mexico, and 6,000 others to key points along with the country, particularly in the Southern border with Guatemala in order to stop the flow of immigrants to the US[28]. The new Mexican administration also sought to expand its collaboration with the American authorities to help stop weapons smuggling. With the creation of the High-Level Security Working Group, the combat against weapon smuggling was pushed forward in the bilateral security agenda as a priority mainly to the Mexican government. In addition, the Secretaría de Seguridad y Protección Ciudadana (Secretary of Security and Citizens Protection) or SSPS, indicated that the National Guard would participate in joint operatives at multiple key border points, namely between Tijuana-San Diego, Ciudad Juarez-el Paso, Reynosa Matamoros and Nuevo Laredo[29]. The outcome of this joint project is nevertheless yet to be reported to the Congreso de la Unión (Congress of the Union)[30], as it is established that this institution will be responsible for evaluating the results of the ESPGR. The criteria of this assessment remain however unclear, as both the ESPGR and the Plan de Desarrollo Nacional (Plan of National Development) fail to provide detailed information about the allocation of resources, means employed, and provisions by which arms traffic will be tackled.

All in all, cooperation efforts between the US and Mexico have refocused as the agendas of the incoming administrations approach borderline security and drug trafficking differently. There have been successful operatives that stem from the Mérida Initiative like the apprehension of “el Chapo” Guzmán in 2014. However, there have also been major setbacks and security breaches that prove an enduring high level of corruption like the escape of “El Chapo” from a Supermax Security Prison the following year (for the second time).

To put things into perspective, as the first left-wing President to ever govern Mexico, AMLO is among the most popular Presidents in the world. However, he’s facing hard criticism as violence is still on the rise, and corruption hasn’t been effectively dealt with as promised during his campaign. In fact, during his first year of government, his administration engaged in a failed operative to apprehend the son of “El Chapo”, Ovidio Guzmán, where a video of the operative was leaked to the public eye and revealed the (fire) power that Cartels hold over the government.

[1] Keegan Hamilton. Felipe Calderon has no Regrets about his Bloody war against Mexico’s Cartels. New York: Vice News, November 22, 2018, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/zmdmzx/felipe-calderon-has-no-regrets-about-his-bloody-war-against-mexicos-cartels consulted in December 2, 2019.

[2]Hamilton also highlights that “throughout the Calderón administration” and “according to research from the University of San Diego, no other country in the Western Hemisphere experienced an increase in homicide as large as Mexico’s”. Keegan HAMILTON. Op. Cit.

[3] Hector ALEE. “Violencia quita a AMLO Diez Puntos de Aprobación”. El Universal, November 15, 2019. https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/violencia-quita-amlo-diez-puntos-de-aprobacion-encuesta, consulted in December 2, 2019.

[4] In fact, the approval ratings of the recent administration (2019) of AMLO (Andrés Manuel López Obrador), lost ten points from August to November (from 68.7% to 58.7%), after a failed attempt to arrest the son of “El Chapo”, Ovidio Guzmán, (this operation will be further analyzed in this work); the second event being the murder of 9 U.S. citizens from the Lebaron family in the state of Chihuahua while traveling back to the U.S. on November the 4th. Hector ALEE, Op. Cit.

[5] Ariadna Ortega. #Fin de Sexenio. Peña Nieto Termina su Sexenio Reprobado por la Mayoría, Mexico City: Expansión, November 24th, 2018, https://politica.expansion.mx/presidencia/2018/11/24/findesexenio-pena-nieto-termina-su-gobierno-reprobado-por-la-mayoria, consulted on November 28th, 2019.

[6] An independent private company in México that specializes in public opinion research through quantitative measurement mechanisms. See Annex 1.

[7] Jonathan Daniel ROSEN and Roberto MARTINEZ ZEPEDA. The War on drugs in Mexico: a Lost War. Reflexiones, 2015, https://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1659-28592015000100153&lng=en&nrm=iso, consulted in November 28, 2019.

[8] Andrea SANCHEZ. “Mexico’s Drug “War”: Drawing a Line between Rhetoric and Reality”, 38 Yale Journal International L. 2013, vol. 38, pp.474.

[9] Andrea SANCHEZ. Op. Cit, pp.471.

[10] José Luis PARDO VEIRAS. 13 años y 250,000 muertos: las lecciones no aprendidas en México. Argentina: Infobae, October 26, 2019, https://www.infobae.com/america/wapo/2019/10/29/13-anos-y-250000-muertos-las-lecciones-no-aprendidas-en-mexico/ , consulted on December 3th, 2019.

[11] Andrea SANCHEZ. Op.cit., pp.471.

[12] “Mexico Murder Rates Rises in First Three Months of 2019”, BBC News, April 22, 2019.

[13] Elements of the federal police, the military police and new recruits were absorbed into the National Guard as established by the coming administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in late 2018 and 2019.

[14] Paul CHRISTOPHER, Clarke COLIN and Serena CHAD. “Mexico Is Not Colombia: Alternative Historical Analogies for Responding to the Challenge of Violent Drug-Trafficking Organizations”. RAND Corporation, 2014, Santa Monica. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR548z1.html. Also available in print form. Consulted in December 4, 2019.

[15] Paul CHRISTOPHER, Clarke COLIN and Serena CHAD. Op. Cit.

[16] Evan PEREZ. Mexican Guns Tied to the U.S.: American-Sourced Weapons Account for 70% of Seized Fireams in Mexico. Reuters: June 10, 2011. http //online wsi corn/article /SB10001424052702304259304576375961350290734 html. Consulted on: May 14, 2020.

9mod=WSJilp_MIDDLENexttoWhatsNoNsSecond#printMode. Consulted on December 5, 2019.

[17] Gabriela MARTÍNEZ, The Flow of Guns from the U.S. to Mexico is Getting Lost in the Border Debate. PBS: July the 2nd, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/the-flow-of-guns-from-the-u-s-to-mexico-is-getting-lost-in-the-border-debate. Consulted on: December 9, 2019.

[18] Decreto por el que se aprueba la Estrategia de Seguridad Pública del Gobierno de la Republica, Mexico City: Diario Oficial de la Federación, 2019.

[19] Cuanto Ganan los Traficantes de Armas en México. Mexico City: RT en Español, 2015.

[20] Jonathan Daniel ROSEN and Roberto MARTINEZ ZEPEDA, Op. Cit.

[21] The Merida Initiative expanded under the Obama-Calderón and Obama-Peña Nieto administrations to focus on a wider scope of topics such as Human Rights, reforming the Mexican criminal justice system, among others.

[22] Eric OLSON. “The Mérida Initiative and Shared Responsibility in U.S.- Mexico Security Relations: How a longstanding initiative has shaped cross-border cooperation”, The Wilson Quarterly, 2017, Washington D.C. https://www.wilsonquarterly.com/quarterly/after-the-storm-in-u-s-mexico-relations/the-m-rida-initiative-and-shared-responsibility-in-u-s-mexico-security-relations/ Consulted on May 15, 2020.

[23] Eric OLSON. Op.Cit.

[24] Clare RIBANDO SELKE, Kristin FLINKEA. U.S.-Mexican Security Cooperation: The Merida Initiative and Beyond. Washington: Congressional Research Center, ROW, R41349, May 7, 2015. Pp. 6.

[25] This pillars addressed (1) improving intelligence and intelligence sharing; (2) support of civilian institutions responsible for maintaining the rule of law and reforming the Judicial system into an accusatorial criminal justice system; (3) Changing the concept of geographical line to one of secure flows, risk segregation and prevent flows of illicit goods while allowing legitimate commerce; and (4) addressing the drivers of violence, investment in prevention and violence reduction efforts, and strengthening communities.

[26] Eric OLSON, Op. Cit.

[27] Clare RIBANDO SEELKE. Mexico: Evolution of the Mérida Initiative, 2007-2020. Washington: Congressional Research Center, ROW, IF10578, updated June 28, 2019. Pp. 2

[28] Lidia ARISTA. Guardia Nacional ha desplegado a 21 elementos para contener la migración a Estados Unidos. El Economista, July 20th, 2019.

[29] Jorge MONROY. Guardia Nacional Realizará Operativos en Fronteras Contra Tráfico de Armas. El Economista. August 6th, 2019. https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/politica/Guardia-Nacional-realizara-operativos-en-fronteras-contra-trafico-de-armas-20190806-0101.html

[30] Name given to the Camara de diputados (Chamber of representatives) and the Senado (the Senate) when acting together as a parliamentary institution.