After the Victory of Aleppo , Will Assad Push South? It is unlikely that Syrian Civil War will end in 2017. Especially since the Syrian Arab Army has retaken the key city of Aleppo after years of fighting. Bashar Al Assad Army is now in control of all major urban centers in the country and have consolidating the gains they have made thanks to Russian and Iranians support. Russia’s claim that they would pull out of Syria because of the enormous cost of operations and the impossibility to reach a decisive victory will have to be taken into consideration in 2017. Russia will try to walk out the Syrian Civil war both with a secured regime for their ally Assad but also with a proud and victorious exit , which would be a huge media victory for the very popular Vladimir Putin. If Putin is able to walk out victoriously from Syria, he will be able to concentrate all its efforts in the Ukrainian Battlefields , where the pro-Russians rebels have been awaiting months to launch an offensive on the weak Ukrainian Governmental Forces.

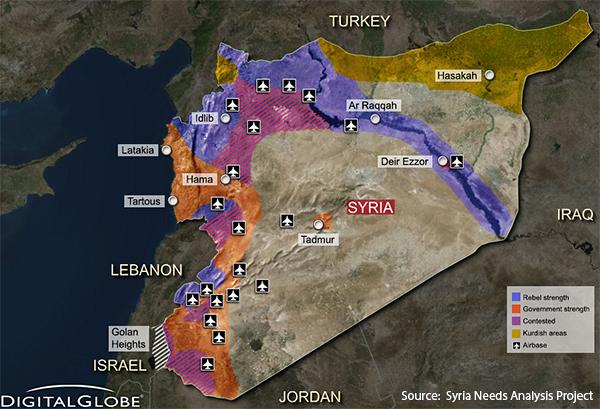

But it is not the end. In 2017 the loyalists have too many battlefields to achieve a decisive victory. Besides the stronghold of Idlib they would have to fight rebels all around the country , especially in the South.

The constraints on the loyalists, however, are but one factor preventing the conflict’s resolution. In 2017, the presence of foreign powers will also complicate the Syrian battlefield, much as it has in years past. The United States will adapt its strategy in Syria, favoring one that more selectively aids specific groups in the fight against the Islamic State rather than those fighting the al Assad government. Washington will, for example, continue to back Kurdish forces but will curb support for rebels in Idlib. The consequences of which will be threefold. First, Turkey, Qatar and Saudi Arabia will have to increase their support for the rebels, including the more radical ones, the United States has forsaken. Second, their support will give radical elements room to thrive, as will the reduced oversight associated with Washington’s disengagement. Third, Russia will be able to cooperate more tactically with the United States and its allies as it tries to exact concessions, including the easing of sanctions, in a broader negotiation with Washington.

Russia as the X Factor

Credit : CNN

Russia’s claim that they would pull out of Syria because of the enormous cost of operations and the impossibility to reach a decisive victory will have to be taken into consideration in 2017. Russia will try to walk out the Syrian Civil war both with a secured regime for their ally Assad but also with a proud and victorious exit , which would be a huge media victory for the very popular Vladimir Putin. If Putin is able to walk out victoriously from Syria, he will be able to concentrate all its efforts in the Ukrainian Battlefields , where the pro-Russians rebels have been awaiting months to launch an offensive on the weak Ukrainian Governmental Forces.

Notably, Russia will cooperate only insofar as it helps Moscow achieves those goals, but given Moscow’s limited influence on the ground in Syria, there is only so much it can actually do. Still, that will not stop Russia from trying to replace Washington as the primary arbiter of Syrian negotiation.

While other powers are preoccupied with the fight against the Islamic State, Turkey will expand its sphere of influence in northern Syria and Iraq, driven as it is by its imperative to block Kurdish expansion. In Syria, the presence of Russian troops will probably prevent Turkey from venturing any farther south than al Bab in northern Aleppo. From al Bab, Turkey will try to drive eastward toward the town of Manbij to divide and thus weaken areas held by the Kurds. Turkey will also lobby for a bigger role in anti-Islamic State operations in Raqqa. Turkey will deploy more of its own forces in the Syrian fight, both to obstruct the expansion of Syrian Kurdish forces and degrade the Islamic State.

There are, of course, some drawbacks to Turkey’s strategy. Namely, it runs the risk of clashes with Russian and Syrian Kurdish forces. Ankara will thus have to concentrate on maintaining closer ties with Moscow to avoid complications on the battlefield, even as it manages tensions with the United States over Washington’s continued support for the Kurds.

In Iraq, too, Turkey will extend its influence in the north – notably, to where the Ottoman Empire’s border was once drawn through Sinjar, Mosul, Arbil and Kirkuk. And as it does, it will compete with Iran for influence in the power vacuum left by the Islamic State’s defeat in Mosul. Baghdad, for its part, will struggle to control Nineveh province once the Islamic State loses Mosul. Meanwhile, Turkey will bolster its proxies to position itself as the patron state of the region’s Sunnis.

Turkey’s resurgence threatens Iran’s arc of influence across northern Syria and Iraq, and Tehran has plenty of ways it can respond. The government will encourage Shiites in Baghdad to resist what they will characterize as a Turkish occupation. It will also rely on Shiite militias to block Ankara by contesting territory and exploiting divisions among Iraqi Kurds. Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Gulf Cooperation Council, who have comparatively less influence Iraq, will rely on Turkey to uphold Sunni interests.

The fall of Mosul will further divide Iraq’s Kurds. The inevitable scramble for territory and influence will pit the Turkey-backed Kurdistan Democratic Party against the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, which is more closely aligned with Iran. Kirkuk, a city and province awash in oil, will be particularly contentious. The KDP will try to keep what it has gained there, while Baghdad, backed by Iran, will try to take it back. This will impede sustainable cooperation in energy production and revenue-sharing operations between Baghdad and Iraqi Kurdistan.