Chad’s Strategic Role in Ending Sudan’s Civil War: Regional Dynamics, Mediation Pathways, and Policy Imperatives

Abstract

The ongoing civil war in Sudan, primarily between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), has not only destabilized Sudan but also strained neighboring countries, including Chad. Given Chad’s geographic proximity, shared ethnic groups, cross-border humanitarian dynamics, and history of diplomatic involvement in Sudanese conflicts, this paper argues that Chad is uniquely positioned to act as a regional mediator and stabilizing force. Drawing on regional security theory, borderland studies, and African conflict mediation literature, this paper explores the potential of Chad to influence peace negotiations, manage refugee flows, and prevent the broader Sahel region from descending into further violence. The study concludes with policy recommendations to empower Chad’s role, underpinned by regional organizations such as the African Union (AU), African civil society organizations (ACSO) and Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD).

1. Introduction

The outbreak of renewed civil war in Sudan in April 2023 marked the collapse of its fragile transition to civilian rule. The conflict between the SAF, led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the RSF, under Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti), has resulted in thousands of civilian casualties, the mass displacement of over 10 million people, and widespread instability across Sudan’s borders. The violence has spilled over into neighboring countries, particularly Chad, which hosts over 1 million Sudanese refugees, many of whom fled from the Darfur region.

Chad’s engagement in Sudan is not new. Historically, it has played a dual role—both as a conduit for peace and, at times, as a participant in proxy conflicts. However, the current civil war presents an opportunity for Chad to adopt a more strategic and stabilizing role. This paper argues that Chad can play a significant role in resolving Sudan’s civil war through diplomatic mediation, regional coalition-building, humanitarian response coordination, and cross-border security management for a better African integration.

2. Theoretical and Analytical Framework

This study uses a multi-theoretical framework combining:

Regional Security Complex Theory (RSCT)(Buzan & Wæver, 2003): RSCT emphasizes that security in one state is interlinked with the security dynamics of its neighbors, particularly in weak or fragile states.

Track-One and Track-Two Diplomacy Models: Chad can operate both as a state actor and via informal channels through shared tribal, religious, and ethnic connections across borders.

Borderlands Governance Theory: Given that the Chad–Sudan border is porous and ethnically interconnected, local actors play crucial roles in peacebuilding, beyond national governments.

By applying these frameworks, Chad’s involvement is viewed not only as geopolitical but also deeply rooted in socio-cultural and humanitarian ties.

3. Strategic Rationale for Chad’s Involvement

3.1 Geographic and Ethnic Proximity

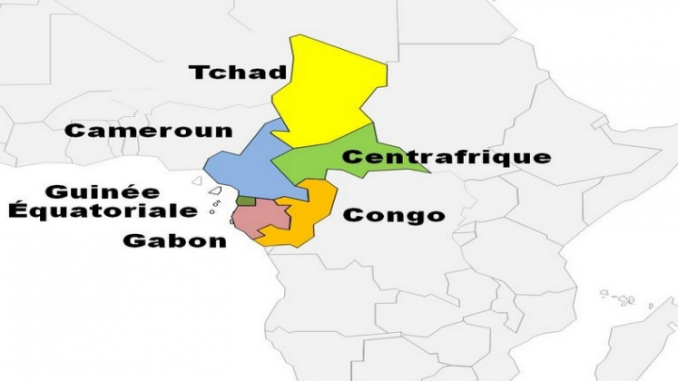

Chad shares a long and porous border with Sudan’s Darfur region, where much of the violence is concentrated. Many groups—such as the Arab, Zaghawa, Masalit, and other nomadic tribes—live on both sides of the border. These groups serve as potential bridges or spoilers in peace processes.

3.2 Refugee Hosting and Humanitarian Stakes

Chad is hosting over 1 million Sudanese refugees, making it one of the largest refugee-hosting countries in Africa relative to its population. Most camps are located in eastern Chad, where resources are scarce and infrastructure weak. This influx puts immense pressure on Chad’s already fragile economy and social services, incentivizing N’Djamena to seek a peaceful resolution in Sudan.

3.3 Military and Diplomatic Credibility

Chad’s military is relatively disciplined and has been an active participant in counter-terrorism operations across the Sahel. Chad also has diplomatic credibility as a past member of the AU Peace and Security Council and has been involved in Sudanese mediation efforts since the early 2000s.

4. Pathways for Chad’s Involvement

4.1 Regional Mediation Role

Chad can serve as a mediator or co-convener in peace negotiations by:

Hosting proximity talks in N’Djamena, with backing from the African Union (AU), ACSO and IGAD.

Leveraging tribal elders and traditional authorities to facilitate Track-Two diplomacy with Darfuri factions and local RSF commanders.

Acting as a neutral ground for refugee-led civil society movements to articulate their demands and influence negotiations.

4.2 Humanitarian Corridor Coordination

Chad can coordinate with the UN, EU, and NGOs to:

Open and secure humanitarian corridorsinto Darfur and Kordofan through eastern Chad.

Facilitate cross-border logistics for food, medicine, and shelter.

Support biometric registration and service delivery to refugees, preventing infiltration by armed groups.

4.3 Regional Security Coalitions

As part of the G5 Sahel and Lake Chad Basin Commission, Chad can:

Push for joint border patrols with Sudan and Central African Republic to prevent RSF movements and arms trafficking.

Share intelligence on mercenary recruitment networks and transnational crime that fund Sudan’s armed factions.

Support a demilitarized buffer zone under AU or UN peacekeeping mandates.

4.4 Neutralizing Proxy Dynamics

Chad’s historical entanglement with both Sudanese regimes and rebel groups must be addressed transparently. To be a credible actor:

Chad must publicly renounce support for any Sudanese faction, both; SAF or RSF elements.

Encourage regional actors (e.g., UAE, Egypt, Libya) to cease military backing of either SAF or RSF.

5. Challenges to Chad’s Role

Despite its potential, Chad faces several constraints:

Internal Political Fragility: Chad itself has enough to do at home; it suffers from weak state institutions, including weak public financial management, insufficient provision of basic services, weak rule of law, lack of transparency and modern technology. The country is facing domestic dissent. And probably such engagement in Sudan risks internal destabilization. Hence, it needs to deal very carefully with such engagement.

Resource Scarcity: Chad also lacks the financial and logistical capacity to unilaterally sustain refugee assistance or mediation processes.

Perceptions of Bias: As we noted earlier that relations between Chad and Sudan are complex and intertwined, encompassing historical, social, and economic ties, as well as recurring tensions and conflicts. All this may compromise its image as a neutral arbiter.

External Rivalries: The involvement of Gulf states, Egypt and Russia complicates regional mediation, requiring Chad to navigate a crowded diplomatic field; which is the most complicated global landscape for Chad, it requires a strategic blend of adaptability, a deep understanding of various perspectives and strong communication.

6. Broader Regional and Global Implications

Chad’s engagement in Sudan can have spillover benefits:

Stabilizing the Sahel: A resolution in Sudan would stem the flow of weapons and fighters that destabilize Chad, CAR, and Niger.

Enhancing African Agency: A Chadian-led peace initiative, supported by AU and IGAD, would enhance African leadership in conflict resolution.

Reducing Migration Pressures: Peace in Sudan would mitigate migration flows through Chad into Libya and the Mediterranean route to Europe.

Deterring External Militarization: Chad’s neutrality can counterbalance external actors and promote non-military interventions.

7. Policy Recommendations

AU-IGAD Peace Process: Position Chad as a co-lead mediator in AU/IGAD-sponsored negotiations, with some African young leaders, EU and U.S. support.

Cross-Border Humanitarian Hub: Establish an international logistics hub in Abéché (eastern Chad) for aid into Darfur.

Security Guarantees: Deploy AU monitoring teams along the Chad–Sudan border to deter cross-border military operations.

Embracing Invincible Defense Technology for Lasting Peace: It’s very important to impliment Invincible Defense Technology (IDT), also known as Transcendental Meditation (TM)-based defense. It is a concept that proposes using the power of collective consciousness through the practice of TM to reduce societal stress and prevent conflict.

International Support for Chad: Provide debt relief, development aid, and logistical support to Chad to sustain its humanitarian and diplomatic efforts.

EAST, West and Soth African Youth Networks (EWSAYN): this unique African youth should be at the forefront of developing and implementing innovative cultural solutions for young people who live in the Sudanese and Chadian borders.

Community-Based Diplomacy: Empower local tribal leaders, women’s groups, and youth networks across the border to play constructive roles in peacebuilding.

8. Conclusion

Chad’s proximity, ethnic ties, and humanitarian exposure to Sudan’s civil war make it not just a bystander, but a critical actor in any path to peace. While challenges persist, a carefully calibrated and internationally supported Chadian role could accelerate the end of hostilities and lay the groundwork for long-term regional stability. In an era where African-led solutions to African conflicts are gaining momentum, Chad’s potential role in Sudan is both timely and transformative.

References

Buzan, B., & Wæver, O. (2003). Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security. Cambridge University Press.

Tubiana, J. (2023). The Political Marketplace in Darfur. Small Arms Survey.

African Union Peace and Security Council Reports (2023–2024).

UNHCR (2024). Sudan-Chad Border Emergency Update.

de Waal, A. (2020). The Real Politics of the Horn of Africa. Polity Press.

IGAD Conflict Early Warning Reports (2023).