On Jan. 12, Gazans protested over the electricity shortage and cast the blame on Hamas. The demonstrations were dispersed by force, but the movement’s leaders understood that their regime could be in danger if they do not solve the energy shortage crisis. Ghazi Hamad, the former deputy foreign minister in the Hamas government, was appointed director of the Energy Authority in the Gaza Strip on March 1. In his new position, he has been entrusted with the most important mission in the Gaza Strip: to find magic solutions to alleviate the shortages of electricity, fuel and gas.

It appears that Hamad will not be able to fully resolve the energy shortages that have plagued the Gaza Strip for more than a decade. However, even Israel’s civil administration staff understands that Hamad is the right person for the job.

Credit : BBC

The electricity problem in Gaza is also of supreme concern to the Israeli security system. For instance, in the Feb. 28 report about the 2014 Gaza war, State Comptroller Joseph Shapira issued a “warning ticket” to the Israeli government for ignoring past and present alerts of the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories regarding the humanitarian crisis looming over Gaza. Head of Military Intelligence Maj. Gen. Herzl Halevy also joined the list of cautioners when he said that a humanitarian crisis in Gaza was inevitable unless appropriate steps would be taken immediately. These remarks were part of a security overview that Halevy delivered at the Knesset’s Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee on March 1.

Indeed, the first step needed to avert such a crisis is to implement swift, effective solutions to the severe electrical shortage that has closed down most of Gaza’s manufacturing sector. Many owners of businesses, large and small — who miraculously succeeded in surviving all the crises, restrictions and wars since the blockade was imposed in 2007 — are now in real danger of bankruptcy. And if they fall, nothing will be able to halt the Gaza Strip’s economic collapse. As a result, a solution to the electricity crisis has become a supreme Israeli interest as well.

“This is a real paradox,” a senior Israeli security source told Al-Monitor on condition of anonymity. “Gaza never enjoyed a regular electrical supply, there were always shortages. But as far as Israel was concerned, and even the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip during [Palestinian President] Mahmoud Abbas’ days, the situation was tolerable. Then, former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert decided to bomb the only power station in Gaza after the abduction of soldier Gilad Shalit [in June 2006]. Even though the power station was fixed later, it never returned to its former level of productivity.”

According to the source, the Palestinians and Israel are still paying the price for Olmert’s mistake to this day, as the former prime minister had arrogantly refused to listen to the warnings of the entire defense system and of his own Defense Minister Amir Peretz.

Thus, Hamad’s appointment is good news for Israel’s security apparatus. While Israel avoids direct contact with the Hamas regime in Gaza, it maintains indirect communication with it via various channels, mainly civilian ones. And Hamad does maintain indirect contacts with Israeli sources that he cultivated over the years — though he will never admit to this publicly. Hamad played a large role in advancing the deal for the release of soldier Gilad Shalit (2011), when he agreed to open a direct negotiating channel with his colleague, Israeli Gershon Baskin.

Hamad is largely held to be one of Hamas’ most pragmatic leaders. He holds a bachelor’s degree in veterinary medicine and is former editor-in-chief of the weekly Hamas newspaper Al-Resalah. When Hamas won the 2006 elections, Hamad was appointed spokesman for then-Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh. When Hamas’ military wing suspected that Hamad and senior Hamas official Ahmed Yousef had been in contact with Israeli representatives in the civil administration for cooperation on the issue of the border crossings, both men were dismissed from their positions. Subsequently, they spent years in Hamas’ political wilderness.

Hamad demonstrated great courage when he criticized the organization’s military wing and its views. In a scathing article that was published in Al-Ayyam newspaper in October 2006, Hamad accused Hamas’ people of hooliganism, because every time the Palestinians agreed to a cease-fire with Israel — during which time the border crossings were opened — one of the Hamas military wing people would shoot a Qassam rocket into Israel, causing the passages to be closed down once again. In the article, despite the life-and-death power held by the movement’s weapon bearers, Hamad called to uproot the roots of the violence.

Now, Hamad is tasked with a most sensitive and important issue for the Hamas movement: the energy crisis. His very appointment seems to imply that Gaza’s new leader, Yahya Sinwar, thinks that Hamad is the right person for the job because of the web of connections the latter has with European and Israeli parties. (Hamad had served as Hamas’ deputy foreign minister and chairman of the Crossings Authority.) Therefore, Hamad has the tools to resolve the electricity crisis. Hamad’s success would be twofold: success for Hamas and success for Israel.

Hamad’s first step would be restoration of the normal functioning of the Gaza power station and the regular supply of fuel. Meanwhile, these are funded mainly by contributions from Qatar and a smaller contribution from Turkey.

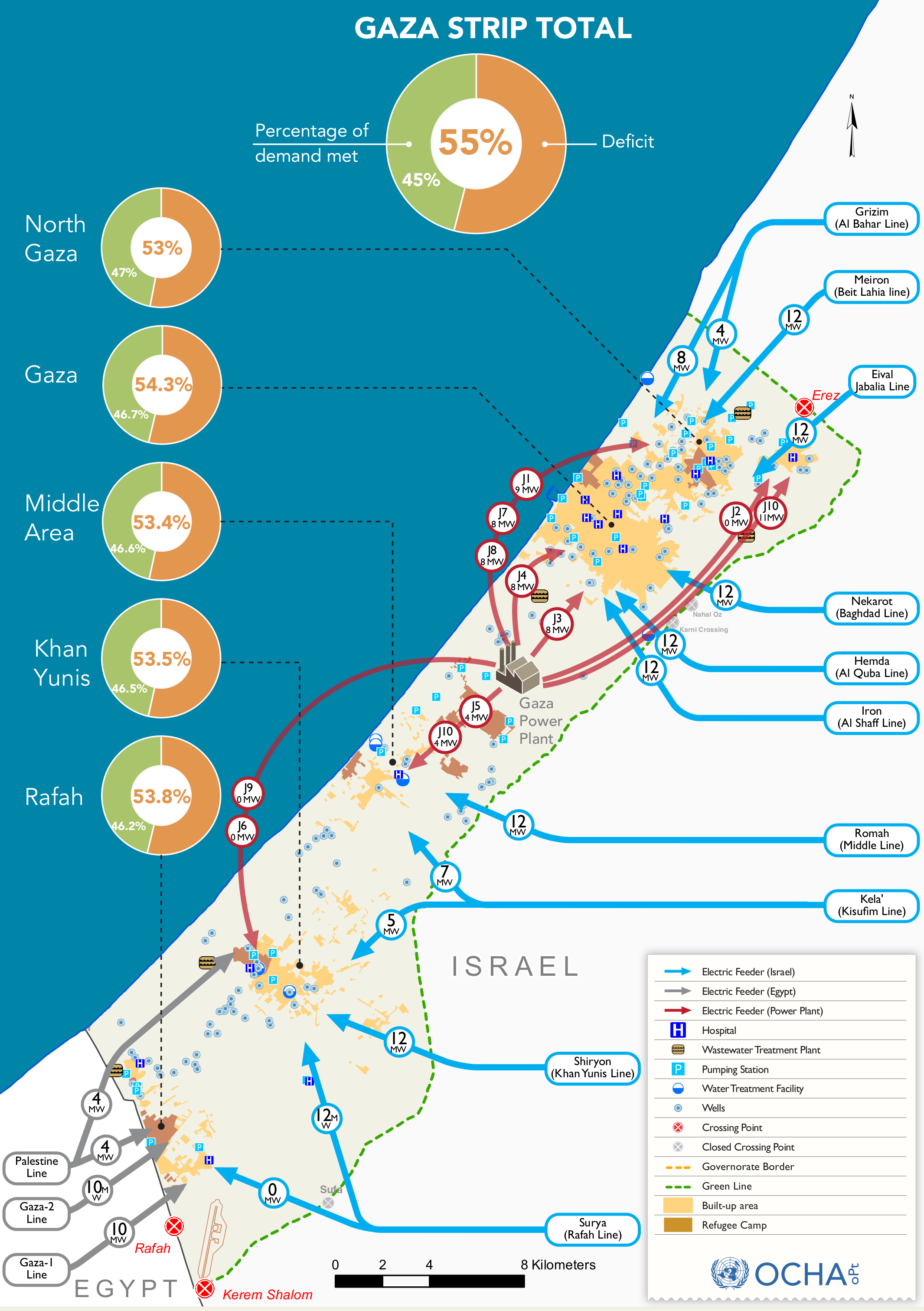

According to data provided by the United Nations, the Gaza power station now supplies 60 megawatts of electricity, only half of its capacity prior to the Israel Defense Forces’ bombardment in 2006. Today, Israel supplies most of Gaza’s electrical consumption (120 megawatts) over power lines. Egypt supplies only 28 megawatts for the southern section of the Gaza strip. To alleviate the electrical shortage quickly, Hamad will have to upgrade the Gaza power station and repair all electrical lines from Israel that need routine maintenance. The only way to successfully carry out these two projects is for Hamad to work in cooperation with the Israeli civil administration, and with the financial assistance of the European Union and Gulf emirate countries, which are expected to donate funds for repairing the neglected infrastructures.

“Ghazi Hamad can deliver the goods,” said the Israeli security source. He added optimistically, “The cow wants to nurse more than the calf wants to suckle.” He probably is referring to Israel, which views the restoration of the electrical system in the Gaza Strip as a supreme security interest of its own.

This article was written by Shlomi Eldar and previously published on Al-Monitor