The Islamic State’s use of natural resources to achieve its strategic goals is nothing new. Oil, one of the group’s biggest sources of funding, plays an especially important role in its calculations — something the countries fighting the Islamic State are increasingly coming to realize. And they have begun to adjust their target sets accordingly. The United States and France, for example, have begun to launch airstrikes against the group’s oil trucks and distribution centers, hoping to hamper its ability to pay for its military operations.

But what is less talked about, although no less important, is the Islamic State’s use of water in its fight to establish a caliphate. Its tactics have brought water to the forefront of the conflict in Iraq and Syria, threatening the very existence of the people living under its oppressive rule. If the Islamic State’s opponents do not move to sever the group’s hold over Iraqi and Syrian water sources — and soon — it may prove difficult to liberate the region from the Islamic State’s hold in the long term.

An Age-Old Conflict

Civilizations have long battled for access to water and founded their empires around great rivers. Historians believe that the ancient Sumerian city of Ur was favored by the empires that followed for its abundance of water and its proximity to the Persian Gulf. Other accounts say the city’s inhabitants abandoned it amid severe droughts and the drying up of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Today, drought and low rainfall compete with the manmade disaster of terrorism to destroy the same, once-fertile swathe of land stretching along the two rivers.

What is Global Affairs?

Governments and non-state actors alike have used water as a weapon for centuries. While the number of full-blown wars over water resources has been lower than one might expect, given how critical water is to any population’s survival, smaller conflicts have been numerous, destructive and deadly. The Middle East has fallen prey to this competition in recent years as states and groups have increasingly shifted from simply cutting off water supplies for a short period of time to diverting water flows or completely draining supplies in an attempt to threaten or coerce consumers.

The Islamic State is no exception. Since the group began expanding its territorial claims in western Syria, it has used water as a tool in its broader strategy of advancing and establishing control over new land. True, the Islamic State has also (and perhaps more visibly) targeted strategic oil and natural gas fields in both Syria and Iraq, but a close look at the group’s movements clearly indicates that the Tigris and Euphrates rivers hold a central role in its planning. Recognition of the Islamic State’s intention to organize its new caliphate around the Tigris-Euphrates Basin may prove helpful in the long-term fight against the group.

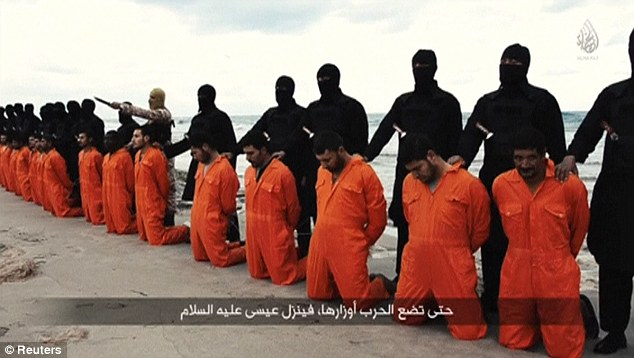

In 2012, the Islamic State emerged from the power vacuum created by the Syrian civil war and made its presence known in the western city of Aleppo. It had little in common with Syria’s other rebel groups, which were primarily focused on fighting the forces of Syrian President Bashar al Assad for regime change. Instead, the Islamic State was a terrorist organization with a clear agenda and strategy: It wanted to build an Islamic caliphate that would, from its perspective, follow the truest form of Islam as decreed by the Prophet Mohammed. Over the following year, the group moved quickly and decisively, cutting a path through Syria and toward Iraq, capturing the key towns of Maskana, Raqqa, Deir el-Zour and al-Bukamal — all of which are positioned along the Euphrates River.

The Iraqi front didn’t look much different; the Islamic State easily captured the river towns of Qaim, Rawah, Ramadi and Fallujah, two of which (Rawah and Ramadi) gave the group direct access to two of Iraq’s major lakes, Haditha Dam Lake and Lake Tharthar. Meanwhile, the Islamic State pursued a similar strategy along the Tigris River, successfully capturing Mosul and Tikrit and attempting to seize other towns and cities along the way. In Iraq the goal was Baghdad, from which the group could rule a caliphate encompassing Syria and Iraq. While the oil and natural gas fields it seized along the way were a means for the group to threaten military forces and make money, the bodies of water and infrastructure were a means to hold the entire region hostage.

Historically, the Euphrates and Tigris rivers have been an important source of contention between Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. The lack of cooperation and coordination between these countries on sharing the mighty rivers has led to a failure to regulate their use and an overconsumption of resources. Consequently, any and all activity by upstream nations regarding the water resources carries the risk of agitating tensions with downstream countries. With no regional coordination and poor security along the rivers themselves, terrorist groups — including the Islamic State — have been able to use water as both a target and a weapon. Not only have they destroyed water-related infrastructure such as pipes, sanitation plants, bridges and cables connected to water installations, but they have also used water as an instrument of violence by deliberately flooding towns, polluting bodies of water and ruining local economies by disrupting electricity generation and agriculture.

Since 2013, the Islamic State has launched nearly 20 major attacks (as well as countless smaller assaults) against Syrian and Iraqi water infrastructure. Some of these attacks include flooding villages, threatening to flood Baghdad, closing the dam gates in Fallujah and Ramadi, cutting off water to Mosul, and allegedly poisoning water in small Syrian towns, to name just a few. Most of these operations are aimed at government forces, designed to fight the military by using water as a weapon against them, though some targeted water infrastructure to disrupt troop movements. Such efforts also often have the added benefit of enhancing recruitment efforts; by allowing water to flow to towns sympathetic to the Islamic State’s cause, or even by simply doing a better job of providing necessary services, the group can attract more men and women to its ranks.

With water at the core of its expansionist strategy, the Islamic State has also ensured that bodies of water and their corresponding infrastructure have moved to the forefront of the ongoing conflict in the Middle East. The control of major water resources and dams has, in turn, given the Islamic State a firm grip on the supplies used to support agriculture and electricity generation. Mosul Dam, for example, gave the Islamic State control over 75 percent of Iraq’s electricity generation while it was in the group’s possession. In 2014, when the group shut down Fallujah’s Nuaimiyah Dam, the subsequent flooding destroyed 200 square kilometers (about 77 square miles) of Iraqi fields and villages. And in June 2015, the Islamic State closed the Ramadi barrage in Anbar province, reducing water flows to the famed Iraqi Marshes and forcing the Arabs living there to flee. While coalition and government forces in both countries have managed to recapture some key water sites, the threat of further damage persists.

At the same time, governments and militaries have used similar tactics to combat the Islamic State, closing the gates of dams or attacking water infrastructure under their control. But the Islamic State’s fighters are not the only ones hurt by these efforts — the surrounding population suffers, too. The Syrian government has been repeatedly accused of withholding water, reducing flows or closing dam gates during its battles against the Islamic State or rebel groups, and it used the denial of clean water as a coercive tactic against many suburbs of Damascus thought to be sympathetic to the rebels.

Finding a Regional Solution

Because of its importance to both electricity generation and agricultural production, water has the power to run or ruin an economy. And since bodies of water often extend beyond any one country’s borders, history shows that the competition for water resources can often only be settled peacefully through regional cooperation. Before Iraq and Syria deteriorated, and groups like the Islamic State arose, countries around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers had only each other to contend with. And in late 2010, the leaders of Turkey, Syria, Lebanon and Jordan appeared to be on the verge of making progress toward setting up an integrated economic region. The countries’ leaders called for regionwide cooperation on tourism, banking, trade and other sectors, and could have laid the foundation for further agreements on the distribution of shared natural resources like water. Though ambitious, the ideas and sentiments behind the proposals had the power to transform the region.

But politics prevailed, as is so often the case, and in less than a year the moment was lost. Had Turkey, Iraq and Syria taken the opportunity to act while political conditions were favorable, they would have found it easier to collectively tackle the Islamic State’s advance later on. Bodies of water could have been labeled regional commons and thus the collective responsibility of all parties, ensuring swifter reactions by the governments involved to protect the water and associated infrastructure from terrorism. This, in turn, would have better protected the people and areas surrounding the rivers and lakes in the region. Of course, it is easy to look back and lament actions not taken, but the point remains that there is still a chance for these countries to come together and start working collectively to protect the water resources they share.

There is no doubt that the Islamic State has a very clear strategy, one that extends even beyond Syria and Iraq and into the wider region. The group has established bases throughout North Africa, following a similar path of controlling key resources and using them as weapons against the populations and governments it seeks to coerce or destroy. It is time that nearby states and the international community re-examine what they know about the Islamic State’s tactics and formulate a new plan of action. Forces fighting the Islamic State must look at the region as a single integrated basin and bring bodies of water — and by extension, the populations dependent on them — to the forefront of their strategies. Water has always formed the core of civilizations; the Middle East — not to mention an Islamic State caliphate — is no different.