Summary

With Turkey and Russia now at odds, Central Asia’s prevailing attitude toward Turkey has changed in recent months. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was scheduled to visit Turkmenistan in October, but a terrorist attack in the Turkish capital led him to delay his trip. Since then, Turkey downed a Russian fighter jet near the Turkey-Syria border, and the resulting tension led to a series of trade spats between Moscow and Ankara. These circumstances will change the atmosphere of Erdogan’s Dec. 11 to Dec. 12 visit to Turkmenistan, during which he will meet President Gurbanguly Berdimukhammedov.

Analysis

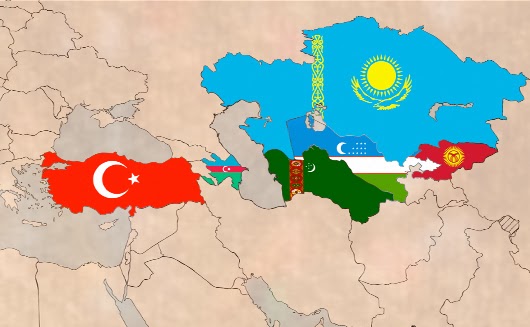

Turkey has had a hot and cold relationship with the Central Asian states. Although Turkey shares ethnic and linguistic roots with four of the five Central Asian states, they have been wary of Ankara’s attempt to extend its influence into the region. Each state has closed Turkish-sponsored schools and nongovernmental organizations that operated in their countries. Turkmenistan, which is arguably the most neutral and paranoid of the Central Asian states, led the regional crackdowns on Turkish influence starting in 2011.

But Turkey remains crucial for Turkmenistan. Turkey is Turkmenistan’s top import partner; Turkish goods — mostly electronic equipment, machinery, processed metals and furniture — make up 26 percent of Turkmenistan’s imports. Since Russia and Turkey’s most recent spat began, some of this trade has been disrupted. A Stratfor source has indicated that trucks of goods from Turkey meant for Central Asia have been prevented from transiting Russia. During the past week, more Turkish goods that once crossed Russian territory have been moved to a route that goes through Azerbaijan and across the Caspian Sea to Central Asia.

Turkmenistan’s vast energy resources are more important, however, in Turkish-Turkmen relations. The Central Asian country holds the world’s fourth- or fifth-largest natural gas reserves (estimates vary). Turkmenistan currently produces some 83 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas per year and exports 58 percent of that, almost entirely to China. Turkmenistan has the potential to produce even more natural gas, but its location has made it difficult to connect with customers.

One of the most eager potential customers is Turkey, which is working within a consortium to construct the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline from Azerbaijan to Turkey, where it will connect with the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline, which will carry natural gas onward to Europe. However, Azerbaijan can fill only a portion of the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline’s 16-bcm capacity, leaving room for another supplier. Turkey, Europe and Azerbaijan have long courted Turkmenistan to fill that role through the proposed Trans-Caspian pipeline. All of these pipelines are the cornerstones of the European Union and Turkey’s Southern Corridor energy strategy, meant to transport natural gas from the Caspian area to Europe, bypassing Russian territory and natural gas supplies.

But Turkmenistan has been wary of partaking in a project that counters Russia, which holds a great deal of influence in Turkmenistan and elsewhere in Central Asia. Moreover, Turkmenistan has been more focused in recent years in fulfilling its natural gas contracts with China. But even as Turkmen natural gas exports to China rise, reaching an expected 45 bcm this year, Ashgabat is looking to diversify its exports, especially because Russia is building a natural gas route to China that could rival Turkmenistan’s. Ashgabat is flirting with the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline, which is fraught with security and financial concerns. Turkmenistan is also holding more discussions with Tehran about using Iran as a transit partner, but Iran is a strong natural gas producer itself and is not likely to help the competition. This leaves the Trans-Caspian pipeline as the last option for diversifying Turkmenistan’s customer base.

Turkey has also grown more interested in the Trans-Caspian because the proposed TurkStream project, which would carry natural gas supplies from Russia, is likely frozen because of the fallout over the Russian fighter jet incident. As the competition between Turkey and Russia grows in a number of areas, Ankara will not want to increase its already considerable energy dependence on Moscow. Pressing Turkmenistan to finally agree to participate in the Trans-Caspian project has become a higher priority for Turkey.

However, Turkmenistan will strive to keep out of the intensifying Turkish-Russian row. Erdogan may feel he can use his strong connections with Turkmenistan’s elite business circles and government officials, but according to a Stratfor source, the current Turkmen president has taken away some of the business groups’ influence and has set up a system of governance that relies more on his decisions than on lobbying from special interests. Ashgabat will remain cautious in any deal that could worsen its position with Russia, even if the deal could bring economic and financial gain.