Henry Kissinger once said that “moderation is a virtue only in those who are thought to have an alternative.” That is precisely Israel’s dilemma. When it shows moderation, its friends may see it as a virtue, but not necessarily its foes, who may equate it with weakness.

Thus, when Israel withdrew unilaterally from Lebanon to the internationally-recognized border in 2000, Hezbollah apparently thought that it was facing a weak Israel across the frontier which could be provoked with scant repercussions. The Palestinians, for their part, seemed to have concluded that Israel could be pressured into further unilateral withdrawals by launching a terror campaign against its civilians, leading, among other reasons, to the so-called Second Intifada.

The effect of Israel’s fierce response to the Hezbollah’s attacks has led to eleven years of relative peace in the Lebanese-Israeli border.

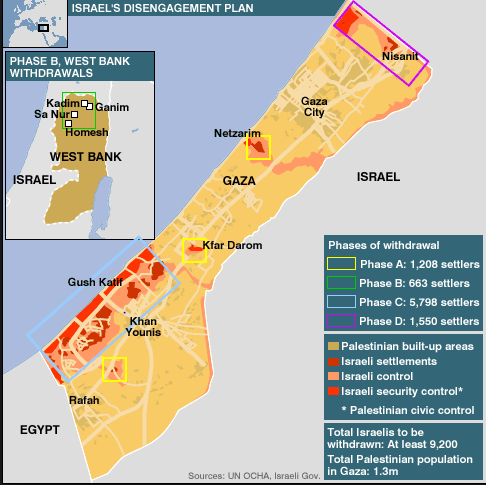

Indeed, when Israel withdrew unilaterally from Gaza in 2005, some groups within the Palestinian Arab camp believed that, as a consequence, further terrorist attacks ought to be perpetrated against Israelis in order to elicit further unilateral concessions by Israel.

In both instances, Israel’s friends applauded the display of moderation by former Prime Ministers Ehud Barak and Ariel Sharon. Their policies were thought of as virtuous. Among Israel’s enemies these were deemed to be a further sign of the country’s feeble resolve to withstand human losses. To be sure, it is possible to draw a clear-cut difference between displaying moderation through unilateral concessions and doing so in the context of a bilateral agreement. Perhaps a show of moderation in the latter case is regarded in a different light even by Israel’s foes.

Peace Agreements and their Perceptions

Thus, when Israel returned to Egypt the entire Sinai Peninsula and agreed to a fully-autonomous West Bank and Gaza, as a result of the Camp David Accords of September 1978 and the Peace Agreement of March 1979, the Arab world did not necessarily identified such a move with weakness. Nor, indeed, did it equate Israel’s concessions to Jordan, as a result of the peace agreement signed by both countries in 1994, with weakness.

Palestine and Israel : The solution nobody wants to talk about.

Both in the case of Egypt and Jordan, Israel’s concessions were undertaken in exchange for peace. In both cases, the Arab leaders concerned were seen to be genuine and serious in their desire to put an end to the conflict, rather than to seek a momentary respite to it, an objective attributed by many in Israel and abroad to Yasser Arafat when he agreed to sign the Oslo Agreement with Israel in September 1993.

Let us now return to Israel’s dilemma. How could Israel display moderation to elicit the support of its friends and the wider international community without losing its deterrence against its foes?

Indeed, Israel has been able to deploy its might against Hezbollah in the Second Lebanon War eleven years ago thanks also – though not exclusively – to the moderate policies it had pursued in the past, which, in a sense, tempered the potential criticism of the international community.

Hezbollah is not merely an armed Lebanese group, but the Lebanese arm of the Iranian army.

The Second Lebanon War

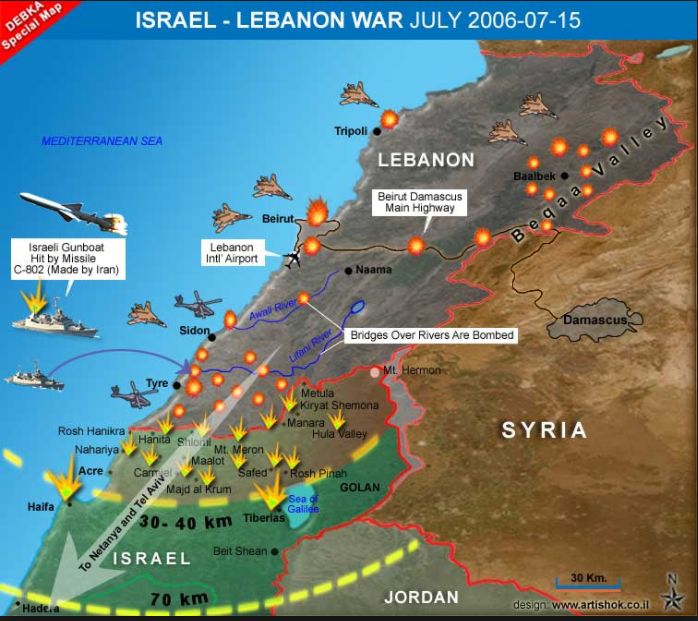

Although Israeli political and military leaders have been criticized in Israel for their decision-making process leading to and during the Second Lebanon War, the effect of Israel’s fierce response to the Hezbollah’s attacks has led to eleven years of relative peace in the Lebanese-Israeli border.

It was no other than Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, who said in the wake of the Second Lebanon War that had he known how Israel would respond to the attack leading to the kidnapping of the Israeli soldiers, he would have refrained from undertaking it. Paradoxically, the Second Lebanon War may have shown that on occasion radical measures can lead to a moderation of Israel’s conflict with its enemies.

So far at least, as a result of the Second Lebanon War, Israel’s northern border with Lebanon has remained mostly quite for the last eleven years. This may be a temporary respite, considering the consistent objective of Hezbollah to bring about the destruction of Israel and its unrelenting efforts to arm itself with missiles that reach all the populated areas of Israel. After all, Hezbollah is not merely an armed Lebanese group, but the Lebanese arm of the Iranian army.

The question with which Israeli decision-makers have to cope is whether a display of restraint, beyond the support from the wider international community, is more conducive to a mitigation of a conflict with an intractable foe or whether a radical action, at least on occasion, can paradoxically lead, as it has with regard to the Second Lebanon War, to such an outcome.

It’s a question that has no mathematical-like answer, but the fact that it can be posed demonstrates that Kissinger’s dictum applies to Israel.