Forecast

- Persistent tension between Moscow and Kiev will encourage Russia to keep looking for pipeline routes to Europe that bypass Ukraine.

- TurkStream will probably remain shuttered until icy Russia-Turkey relations thaw.

- Given numerous political hurdles, South Stream’s prospects are similarly bleak.

- Nord Stream II could see more success, though Gazprom’s own financial problems and stronger European regulations may still stand in the way of its completion.

Analysis

Editor’s Note: Stratfor closely monitors the ebbs and flows of world energy. Aside from production, the transportation of crude oil, natural gas and petroleum products is of paramount concern for oil-producing nations. For energy consumers, transit routes are indispensible lifelines. A huge amount of the world’s energy is transited through pipelines, across the Eurasian landmass in particular. In this periodic series we will examine some of the most geopolitically significant pipelines running through Europe and Asia. In this installment, Stratfor examines Russia’s options for finding a pipeline route that bypasses Ukraine.

Russia is searching for new ways to send its natural gas to Europe, but with little success. Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke with Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi on Jan. 8 about Italy’s involvement in several of Moscow’s proposed energy projects, including the Nord Stream II pipeline, some aspects of which Rome has vocally opposed. The meeting came amid rumors that Russia had also resumed negotiations with Bulgaria over the defunct South Stream project, which was suspended in December 2014. Both governments denied the rumors.

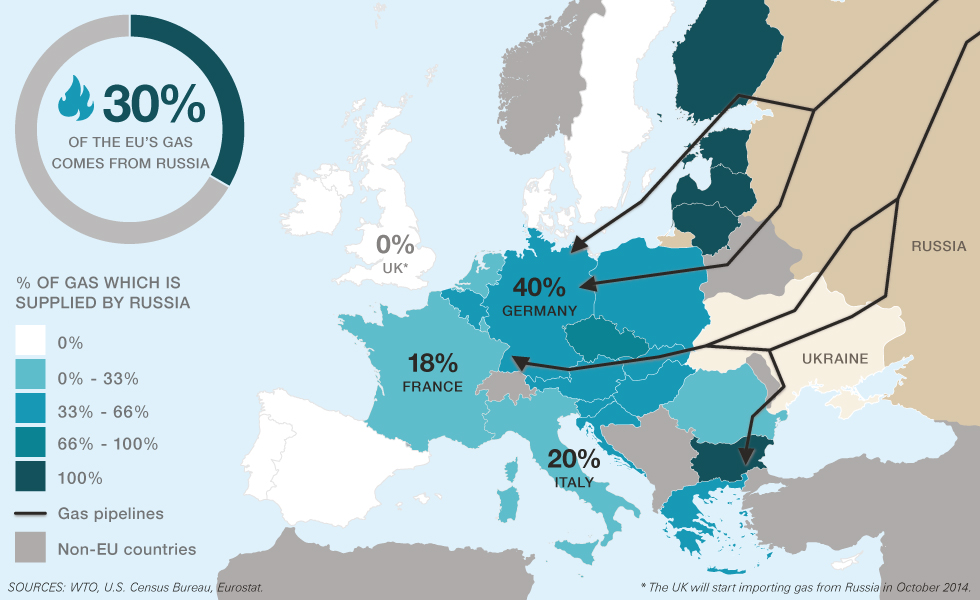

With the Russia-Ukraine relationship on the rocks, Moscow is desperate to find a pipeline route to its Continental consumers that does not pass through Ukraine. However, every possible alternative on the table faces significant political, economic or technical constraints. With Russian energy giant Gazprom in financial distress and the European Union determined to break the firm’s near-monopoly hold in Central and Eastern Europe, fiscal pragmatism may force the Kremlin to re-evaluate its ambitious energy goals.

Ukraine: A Troublesome Partner

Moscow’s strained relationship with Kiev took a turn for the worse on Jan. 1, when Ukraine upped its transit tariffs on Russian natural gas passing through the country. Previously, Gazprom paid $0.07 per million British thermal units (mmbtu) of natural gas for every 100 kilometers (62 miles) it traveled. (The main segment of the Urengoy-Pomary-Uzhgorod pipeline in Ukraine is about 1,160 kilometers long.) Now, Gazprom must pay a fee of $0.35 per mmbtu of natural gas that enters Ukraine and $0.48-$0.93 per mmbtu that exits the country.

Meanwhile, Ukraine is also getting ready to fully implement its new “On the Natural Gas Market” law on April 1. The legislation, which the Ukrainian parliament adopted last April, will overhaul the country’s natural gas regulatory market and bring it in line with the European Union’s Third Energy Package. Ukraine has been working toward these reforms since it joined the Brussels-led European Energy Community in December 2010. One of the organization’s goals is to extend legislation aimed at breaking Gazprom’s energy monopoly to non-EU countries in the bloc’s immediate periphery, including Ukraine and the Balkan states. Ukraine’s involvement in the European Energy Community and its EU association agreement indicate that it is finally taking concrete steps to integrate its economy and energy market with those on the Continent.

These developments have only increased Russia’s desire to pursue other pipeline routes that bypass Ukraine. TurkStream and South Stream were designed to do just that for markets in Southern Europe, while Nord Stream I and II do the same for Northern and Central Europe. Gazprom hopes to have at least one of these projects constructed by the end of 2019, when Russia’s transit contract with Ukraine ends. But given the many problems that Gazprom has consistently encountered with each of them, it looks increasingly unlikely that the firm will be able to have the infrastructure it needs in place by the start of 2020.

TurkStream

In the span of a year, the TurkStream pipeline has shifted from a fast-tracked proposal to a project on ice. For much of 2015, TurkStream was stalled by a deadlocked Turkish parliament. When the Justice and Development Party regained its legislative majority in November, it appeared that a major obstacle to the pipeline’s progress — getting approval from the Turkish parliament — had been cleared. However, this sense of optimism was quickly dashed when two Turkish jets shot down a Russian Su-24 warplane near the Turkey-Syria border on Nov. 24, 2015. Diplomatic ties between Moscow and Ankara have remained soured ever since, jeopardizing the future of the TurkStream project and prompting Gazprom to turn to other options, including South Stream and Nord Stream II.

South Stream

A year ago, Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller proclaimed: “South Stream is dead. For Europe there will be no other gas transit options to risky Ukraine other than the new ‘Turkish Stream’ pipeline.” At the time, this seemed to be the final nail in South Stream’s coffin. But with numerous political barriers standing in the way of TurkStream’s progress, rumors have begun to trickle out of Bulgaria that the South Stream pipeline may be resurrected. Though both Moscow and Sofia have denied the allegations that they are actively discussing the revival of South Stream, there are certainly reasons that the two might start the project back up.

Despite South Stream’s cancellation, Sofia has remained open to the pipeline proposal. On Jan. 11, Bulgarian Economy Minister Bozhidar Lukarski reiterated his government’s official position: South Stream has been suspended, not canceled. Bulgaria has been attempting to establish itself as a natural gas hub for Southern Europe for some time. As the poorest member of the European Union, it is also looking to attract as much investment and create as many jobs as it can. And indeed, Bulgaria is already making tangible progress toward its goals. On Dec. 11, after a meeting between Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borisov and German Chancellor Angela Merkel on natural gas markets in the region, the European Commission agreed to set up a working group to support the formation of a natural gas hub in Southeastern Europe. In fact, this development is what sparked the initial claims that South Stream was back on the table.

At the same time, investors made a final decision Dec. 10 to build the Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria pipeline, which is designed to deliver 5 billion cubic meters of natural gas from Greece to Bulgaria. Though each of these moves has put Bulgaria closer to achieving its new role in the region’s energy market, it will still need to find other sources of natural gas to turn the dream of a Balkan energy hub into a reality. The South Stream project and the Russian natural gas it would carry could be one such source.

That said, Russia and Bulgaria would still need to overcome a number of hurdles to pick the South Stream project back up. First, they would need the approval of the countries the pipeline would transit, including Serbia, Hungary and Italy. Moscow’s relationships with those countries are relatively friendly at the moment, but gaining their approval and organizing the project would still take time. Gazprom, which bought out the shares of Eni, EDF and Wintershall to become the sole stakeholder in the South Stream Transport BV consortium, will have to find new partners to join it or fund the project itself. The company is also still sorting out its dispute with Italy’s Saipem over debts owed after Gazprom canceled a pipe-laying contract.

Second, Russia would still need to get Turkey’s endorsement for the project, since the original plans called for South Stream to avoid Ukraine by running through Turkey’s waters in the Black Sea. Moscow’s only alternative would be to challenge Ukraine’s maritime claims by expanding Crimea’s exclusive economic zone — a risky move that the Kremlin is unlikely to make, since it would almost certainly prompt the United States and Europe to increase sanctions against Russia. Thus, no matter how interested Bulgaria is in pursuing the South Stream project, its outlook remains bleak.

Nord Stream II

Unlike TurkStream and South Stream, Nord Stream II would not deliver Russian natural gas to Southern Europe. Instead, it would expand Gazprom’s market share in the Continent’s north, especially in Germany and the Czech Republic. The project would enable Russia to take advantage of Germany’s recent efforts to move away from nuclear energy, as well as declining output from producers in the North Sea, such as the Netherlands.

But like Nord Stream I, Nord Stream II has received mixed support from Europe. The pipeline would signal Russia’s persistent energy ties to Germany at a time when Berlin is defending the continuation of sanctions against Russia because of events in Ukraine. As one would expect, countries that firmly oppose any sort of Russian encroachment on the Continent — perceived or otherwise — have pushed back against Nord Stream II. These countries include Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia and Slovakia.

Strangely enough, Italy also counts itself among the pipeline’s strongest European critics. Although Nord Stream II undermines Italy’s energy security to a minor degree, it is unlikely that Gazprom would stop sending natural gas through its Ukrainian pipeline unless it could continue supplying its second-largest customer on the Continent, Italy, through other means. Still, Nord Stream II would not easily provide those means, at least not to the extent that South Stream and TurkStream could.

Nevertheless, Italy’s opposition likely stems from Prime Minister Matteo Renzi’s irritation with the actions of Germany and the European Union as a whole. In recent months, Renzi has more openly challenged Berlin and Brussels on the issues of sanctions, immigration and security priorities. Therefore, Renzi’s resistance is likely as much a statement against Germany, which supported the Nord Stream project while opposing South Stream, as it is against the pipeline itself. Putin reportedly may be trying to secure Renzi’s support — or at the very least, indifference — for Nord Stream II in exchange for allowing Italy to be involved in the project. Regardless of the prime minister’s stance, though, Italy’s Saipem stands a good chance of being selected for the job, since it is a premier offshore contractor and was chosen to build Nord Stream I.

Despite the fierce political debate over Nord Stream II, the countries that opposed it have few ways to actually block the pipeline from being constructed. Gazprom needs the approval of only Russia, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Germany, since the pipeline route passes through their waters; the European Commission has no formal mechanism through which to shut down the project. Nor does it necessarily have the will. The commission’s official stance has remained consistent: As long as Nord Stream II adheres to European regulations, it will not try to halt the pipeline’s construction.

Of course, the enforcement of European regulations presents a difficult roadblock to overcome on its own. In essence, Nord Stream II and all of its connecting onshore pipelines will have to satisfy the Continent’s third-party access provisions and other requirements. These rules created problems for Nord Stream I by limiting Gazprom’s use of the OPAL pipeline — one of the two offloading pipelines for Nord Stream at the German coast — to 50 percent. This in turn prevented Gazprom from operating Nord Stream I at its full capacity. In the case of Nord Stream II, Gazprom could and would negotiate for exemptions to circumvent the rules, as it ultimately did for Nord Stream I. However, Brussels would agree to those exemptions only if Gazprom made significant concessions to reduce its monopolistic hold on the European energy market.

In the End, Profit Is What Matters Most

With TurkStream talks at a standstill and South Stream stalled indefinitely, Nord Stream II may simply serve as the path of least resistance for Russia as it looks for another pipeline to Europe. Gazprom has sped up projects in Russia that will expand its capacity in the Baltic Sea so that it can theoretically feed the massive Nord Stream II pipeline someday. Its efforts include transferring 330,000 metric tons of pipeline, originally intended for the suspended Southern Corridor project, to the Bovanenkovo-Ukhta and Ukhta-Torzhok pipelines. These pipelines are intended to eventually feed into Nord Stream II from fields in the Yamal Basin.

However, Gazprom’s financial problems and a crackdown by Russia’s Federal Anti-Monopoly Service may have already slowed these plans. On Dec. 29, Gazprom canceled a $2.2 billion tender for the construction of roughly half the Power of Siberia pipeline. The following day, it canceled another tender for the Ukhta-Torzbok II pipeline, and on Jan. 11, the company bailed out of three tenders that collectively totaled about $171 million. In light of these funding issues and with little relief from low energy prices in sight, the calculus of cash-strapped Gazprom will likely change. Profit will become the most important factor in determining Nord Stream II’s future as Gazprom adjusts to the reality of a more competitive energy market in Europe.