Grand Strategy has long been an important framework for examining state behavior, and for states to shape their behavior. Even without that moniker, it has been a concept long studied by the likes of Machiavelli and Sun Tzu: how can a state most effectively employ its resources to reach its aims? Naturally, over time this idea has been expanded upon. Liddell Hart assumed a militaristic focus, whereas scholars and historians like Paul Kennedy and Barry Posen have later included economic and diplomatic means.

Despite these developments, the world is accelerating beyond this conceptual framework. With its persistent state-centric and militaristic tendencies, Grand Strategy risks being left behind by the 21st century. With the rise of non-state actors and global threats like climate change, upheavals of political systems, and the emergence of cyberspace, our definitions of Grand Strategy are not merely old – they are rendering themselves obsolete.

With this in mind, is it possible for Grand Strategy to adapt to this new global landscape? Relying on its traditional definitions, it seems unlikely that Grand Strategy will survive as a conceptual framework for state policy on the global level. The leeway allowed by the Emergent Strategy school of thought, however, might just hold the key to translating the ideas behind Grand Strategy into 21st-century language.

A Discussion on Grand Strategy

Before I begin discussing the possible future role of Grand Strategy, a brief discussion of the oft-misunderstood term Grand Strategy is in order. Broadly speaking, Grand Strategy is the sum effort of a state’s capabilities towards a set of aims. This requires three fundamental components: the organization of resources, a set of aims, and a prioritization of those aims.

Beyond this, one must consider the Classicist versus International Relations theorists. The classicists espouse military-centric views. Liddell Hart, a famous theorist, defines Grand Strategy as the coordination of state resources toward the political aims of the war. [1] Posen describes it as a “political-military means-ends chain.” [2] A last crucial component is the articulation of these aims and efforts. [3]

In the International Relations school, Grand Strategy is broader – a kind of ‘meta-strategy’. [4] Williamson Murray et al. expand Grand Strategy to resources and means beyond those pertaining to the military in both times of war and peace. [5] Hal Brands offers the elusive “grand strategy as the intellectual architecture that gives form and structure to foreign policy.” [6] In essence, International Relations theorists view Grand Strategy as the employment of any state resource towards articulated aims.

On the other hand, several theorists call for a revision of Grand Strategy. Rather than constituting a detailed plan that must be followed to the letter, Grand Strategy emerges over time, they argue. Thus, Grand Strategy should be looked at as a form of institutional learning, a best practice that is honed over time. After all, when are these plans ever followed to the letter, and when do they yield the intended results? Secondly, articulation is often emphasized in traditional Grand Strategy theory. Threats must be identified and prioritized, and a plan to address them articulated. This, too, often changes, especially in the volatile global and regional politics of today. Mintzberg argues that where Grand Strategy concerns control, Emergent Strategy concerns developing intentions from learning. [7]

Otto von Bismarck is often used as a reference point regarding the above. In a volatile European landscape, he deftly maneuvered his opponents to pursue his two aims: German unification under Prussian leadership, and European peace to protect that unification. Both were achieved. While Bismarck did indeed have a clear conception of his aims and prioritization of them, he was also a known improviser and opportunist, seizing opportunities and exploiting events as they appeared. These ideas embody the school of Emergent Strategy, with the latter representing an important component of foreign policy in today’s volatile global landscape.

Changes in Grand Strategy

How can the above theories and interpretations fit into the 21st century? For the most part, they do so poorly. Numerous large phenomena contribute to this: climate change, terrorism and insurgencies, and the cyberspace. Lastly, though possibly a less robust trend, we are currently in the middle of a brutal upheaval of the political norms established in the 18th and 19th centuries. With the rise of populist politics, the way leaders and governments make decisions may also be changing.

The primary change occurring in Grand Strategy is its scope. In the past, threats to a state’s security, as well as their severity, have been identified and assessed by individual states, relying on their perception and prioritization. This framework is unlikely to unravel altogether, but the world is nevertheless changing. Climate change, for instance, is a global threat demanding global action. This is a threat that affects all states – admittedly to different extents. Its global nature means that it is not a threat that affects only selected states, as opposed to a rival state or an insurgency. Napoléon was perceived as a major threat to the UK and Prussia, but Qing China would not view the French Empire the same way. With climate change, these geographical boundaries are erased.

Secondly, Grand Strategy has tended to be rather state-centric. This debate has been raging among International Relations theorists for some time now, spawning several theories beyond just Realism and Liberalism. In the realm of Grand Strategy, the pervasive focus on states prevails. Emphasis is delegated to the states in a system, their actions, and against whom those actions are directed. In the past four decades or so, however, a series of non-state actors have risen to prominence. Terrorism has become a global phenomenon, and insurgencies emerge from all nooks and crannies.

Most prominently, ISIS has been a major foreign policy issue for most Great Powers since the early 2010s, despite being far removed from most of them. Even in the twilight decades of the 20th century, dealings with or against non-state actors grew ever more commonplace in the realm of security policy. Consider, for instance, the Iran-Contra Affair, US support for the Mujahedeen in Afghanistan, or the alleged ties between the CIA and Latin American drug lords in the 1980s.

On top of this, the world has attempted to impose upon itself a global order in the form of supranational and international organizations of various kinds. The UN, the EU, NATO, and the OECD stand out as prominent examples of organizations with different mandates and aims. They have become important players on the global stage, with their own practices and aims. This contributes to a global landscape where state-centrism makes ever less sense.

A note is also due to an interesting current trend: the rise of populist politics. Seeing as we stand amidst this development, it is difficult to assess its permanence, but it nevertheless has the potential to affect Grand Strategic practice. The US is home to a well-established foreign policy executive, yet the presidency of Donald Trump has caused quite the furor in Washington. Take, for instance, his recent decision to abandon their Kurdish allies along the Syria-Turkey border, opening up for Turkish military action, much to the consternation of the aforementioned foreign policy executive.

Likewise, populist and far-right forces have been on the rise in Europe. While their political impact has not been quite as significant as many feared, these forces have nevertheless posed a challenge and a threat to, for instance, the EU, and many countries’ foreign policy in general. Whether this is a lasting trend or not remains to be seen, but there seems to be an emerging trend of diversifying governments, admitting a wider range of aims and priorities. This could very much have an impact on how these states organize themselves and their resources.

Finally, the rise of cyberspace has brought with it a whole new dimension of security. The invention of the plane, the tank, ICBMs, and nuclear warheads all have had tremendous impacts on the physical security landscape. After WWI, military strategy underwent dramatic changes in a rather short time. Digital development, however, has gone a step further and created a whole new security dimension. It is not physical, and no government can monopolize its power in it.

The strategic shifts that came after the invention of the plane, the tank, long-range missiles, and especially nuclear weapons were significant indeed but were largely limited to the military sphere. Cyberspace is all around us and has become integral in the lives of billions of people, alongside governments. This makes it an incredibly powerful tool, but our reliance on it is also a target: its destruction or neutralization comes with grave consequences. This means that governments now need to consider this virtual space, in which every actor is equal in their security deliberations.

The Future of Grand Strategy

For the past few decades, the world has witnessed political and technological upheavals the likes of which have rarely been seen. Nevertheless, these developments cannot quite compare with the impact of the upheavals we are currently witnessing. In particular, technological developments are moving at a pace so rapid that most of us – individuals, interest groups, or governments – are simply unable to keep up.

I am sure that many of us remember with horror the attempts of the US Congress to question first Mark Zuckerberg, then Google CEO Sundar Pichai. The procedure was an utter disaster. Amidst attempts by members of the hearing to question Zuckerberg on data rights, Senator Ted Cruz went completely off course and launched into a string of incoherent questions on political biases. Similarly, no one on the committee questioning Pichai seemed to understand how the internet and Google truly function.

This is but an extreme example of a frightening trend: governments have started realizing the threat potential in Cyberspace, yet they fail to understand both the nature of these threats and the Cyberspace itself. Thus, they cannot effectively ascertain the nature or the severity of emerging threats, nor craft responses to them.

Likewise, the past four decades have failed to produce any effective strategy against terrorism, a threat that most governments fail to truly understand. For the most part, they cannot even agree on a definition of what constitutes terrorism. Both suffer from an excessive focus on states. States must form the reactions to threats posed by other states.

In terms of function, composition, and action, most states are nearly identical – despite power disparities that are more or less significant. This means that states can more effectively address each other. They are far apart, but France and India can find much common ground, and pursue very similar ends. France, however, fails to truly understand ISIS, like most other countries. Nevertheless, ISIS also posed a threat to France, despite the distance separating them. Threats are becoming global, which brings new and unfamiliar threats to our doorsteps. Effectively assessing and facing these threats can be challenging.

A short answer here is a move from traditional ideas about Grand Strategy to emergent strategy. Classicist and International Relations theories of Grand Strategy are too archaic and too rigid for the ‘liquid modernity’ in which we find ourselves today. In order to succeed in the flexible 21st century, states must adapt to a system where change is the only constant.

Emergent Strategy provides a framework for studying state behavior and opens up opportunities for state learning. This, in turn, can provide states which much needed flexibility in the face of emerging challenges. Mitzen proposes that the very idea of Grand Strategy itself is a forced concept: the gap between plan and reality is simply too wide. [8] With the changes we are currently witnessing, this may be good advice to take to heart.

Rather than committing to ill-advised plans, states need the agility to navigate a multi-dimensional threat landscape and identify threats. To do this, and to assess them, rigid plans must be abandoned in favor of a simpler and more streamlined system that makes room for flexibility. Traditional conceptions of Grand Strategy do not do this. Emergent Strategy might.

References

[1] Hart, B. H. Liddell. Strategy (2nd ed.). London: Faber & Faber, 1967: 322.

[2] Posen, Barry R. The Sources of Military Doctrine: France, Britain, and Germany Between the World Wars. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1984: 13.

[3] Martel, William C. Grand Strategy in Theory and Practice: The Need for an Effective American Foreign Policy. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 2015: 339, 353.

[4] Balzacq, Thierry, Dombrowski, Peter, and Reich, Simon. “Is Grand Strategy a Research Program? A Review Essay.” Security Studies (2018): 14 – 15.

[5] Murray, Williamson and Grimsley, Mark. “Introduction: On Strategy.” In The Making of Strategy: Rulers, States, and War, edited by Williamson Murray, MacGregor Knox, and Alvin Bernstein, 1 – 23. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994: 1 – 23.

[6] Brands, Hal. What Good Is Grand Strategy? Power and Purpose in American Statecraft From Harry S. Truman to George W. Bush. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014: 3.

[7] Mintzberg, Henry, Ahlstrand, Bruce, and Lampel, Joseph. Strategy Safari: A Guided Tour Through the Wilds of Strategic Managements. New York: The Free Press, 1998: 189.

[8] Mitzen, Jennifer. “Illusion or Intention? Talking Grand Strategy Into Existence.” Rhetoric and Grand Strategy 24, (2015): 62.

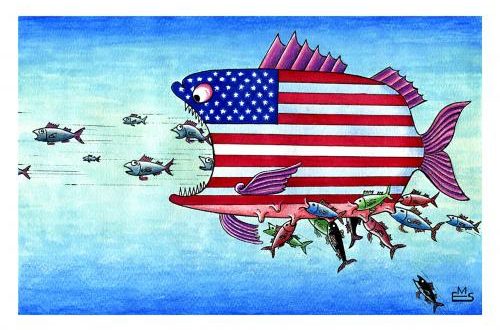

Image credit: Mattis, Jim. “A New American Grand Strategy.” Hoover Institution. https://www.hoover.org/research/new-american-grand-strategy (Accessed 23.10.2019)