Much more influential than Samuel Huntington, Zbigniew Kazimierz Brzeziński (ZKB) has taken up some of his theses, reformulating them from reference bases acceptable to the various trends of the US elites. More than Huntington, brilliant but isolated, ZKB, cynical and powerful, embodies the alternative line to neo-conservatism within American imperialism. Today, as an advisor outside President Obama’s organizational chart, he is driving a new strategic direction for US foreign policy: more calculating, more cautious than the neocons, he shares their imperialism, but not their unilateralism. His thinking is not an alternative to the ideology of the “clash of civilizations”, but an alternative formulation of this ideology.

Its strength: networks. ZKB has an ideal profile to build a bridge between neoconservative and realistic conservative circles: originally from the Democratic Party, of Judeo-Polish origin[uncertain Jewish origin], driven by a notorious aversion to Russia, it can afford to criticise Jewish circles and the American left more easily than a right-wing WASP, such as Huntington – which is not without importance in the current US context. Friend of David Rockefeller, with whom he co-founded the Trilateral Commission in 1973, he has the almost unconditional support of the “big business”, whose interests he has always defended (he is the inventor, among other things, of the theory of “tittytainment”, according to which the future society will ensure the domination of the very rich by locking 80% of the population in the generalized abêtissement). A theorist of positive inequality, he is one of those extreme right-wing men (in reality) who understood that a pseudo-progressive discourse was now the necessary mask for fascism. His “coup d’éclat” dates back to the late 1970s when, advising President Carter, he destabilized Afghanistan, forcing the Soviets to engage in a bait and switch. There is no doubt that its level of reflection is much higher than the average of the neoconservatives of the “Project for a New American Century”.

In 1997, he wrote “Le Grand Echiquier”. Following the attacks of 11 September 2001, after which it became difficult to advocate too openly for support for Islamists in order to use them as a weapon of destabilisation, he proposed an updated theory with “The Real Choice: World domination or world leadership”. Basically, however, this second book does not modify the theses advanced in “Le Grand Echiquier”.

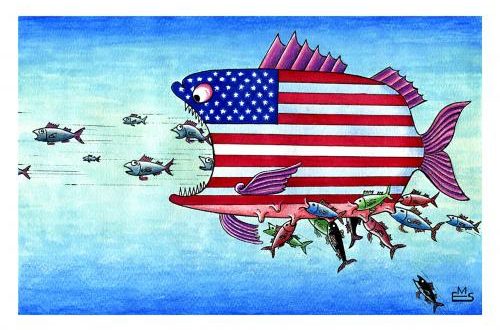

Unlike Huntington, ZBK agrees, as do the members of the PNAC, that the USA should not tolerate the mere existence of a geostrategic rival. However, for the sake of realism, it places this objective within a multilateral framework. As a supporter of a USA-Europe alliance, he wants the West as a whole to remain predominant, and the USA to be predominant within the West as a whole. The version of the “clash of civilizations” promoted by ZBK therefore implies the incubation of a framework of preconception that is significantly different from that desired by the neoconservatives: the USA is not for him the “policeman of the world”, but the regulator of a predominant Western bloc. This divergence explains why American power’s communication strategies have evolved since Obama’s arrival in business, with “soft power” replacing “hard power” (military conquest) as a method positively presented by the dominant media.

ZBK’s strategic analysis takes up the basic assumption of traditional geopoliticians: Eurasia is the centre of world power, since it represents half of the human population. The key to controlling Eurasia, he explains, is Central Asia. And the key to controlling Central Asia is Uzbekistan (remember that American forces deployed after 11 September 2001, first in this former Soviet republic). In “Le Grand Echiquier”, ZBK confirms that a long-term strategy was deployed as soon as the USSR fell to encourage American settlement in this area, a strategy based on economic settlement and Russia’s weakening.

Unlike the signatories of the PNAC, a group that concealed its objectives behind unilateralist and pseudo-patriotic warfare, ZBK had the courage, in “Le Grand Echiquier”, to recognize that the “camp” for which it was fighting was not the America of the Americans. It is globalized capitalism – that, and that alone. The objective of the conquest of Central Asia must be, according to ZBK, to ensure the victory not of America itself, but rather of a New World Order entirely dominated by large multinational companies (mainly Western).

” The Grand Chessboard ” is a true hymn to the governing bodies of economic globalization (World Bank, IMF). ZBK is the first patriot in Richistan – a country overhanging all the others, where only the very, very rich live.

“The Grand Chessboard ” is generally an interesting book because ZBK, with a rather remarkable cynicism, bluntly admits the manipulations that neoconservatives, in general, have carried out by hiding them behind a curtain of Americanist smoke. A man of “big business”, he does not have to worry about the reactions of the “moral majority” which was one of the foundations of neoconservatism. That is why he admits, as a given fact, that America’s anthropological base is destined to diversify, to the point of becoming a perfect reflection of global diversity. And to unify this totally disparate base in terms of identity, he advocates (in 1997) a “new Pearl Harbor”, which would make it possible to identify a fantastical enemy (Islamism for example), a negative integrator of a totally unstructured American population.

The reading of the “Grand chessboard” confirms that there has been competition among American elites for more than a decade between a line driven by the “pro-Israel lobby” and another line, defended by ZBK, which pays very little attention to the future of the Jewish state. For ZBK, the main objective of the great US strategy must be, at the beginning of the 21st century, to fight against the China/Russia alliance, if possible by preventing it from forming, otherwise by limiting its scope and power. In this perspective, ZBK (perhaps motivated here by its notorious Russianophobia) considers that the main threat comes from Russia, insofar as, although less economically powerful than China, it has more means to achieve full sovereignty. It advocates the encirclement of Russia by the gradual establishment of military bases, or in the absence of friendly regimes, in the former Soviet republics (including Ukraine), as well as the weakening of Moscow by the looting of its economy (remember that the book was written in 1997, when the oligarchs shared privatised Russian companies, one year before the crash of 1998).

With a cynical frankness, ZBK admits in the process that America is, in his opinion, “too democratic internally” to be sufficiently autocratic internationally. He draws the conclusion, crucial for anyone who wants to understand his thinking formula, that America must favour strategies of influence in order to be autocratic without this being seen by the American population itself.

It must therefore be understood that ZBK’s subsequent statements, from 2004 onwards, against the “war on terrorism”, do not reflect on its part a refutation of the reality of this war – it knows perfectly well that it has never been anything other than a pretext, and it has itself advocated the use of this pretext. His positions reflect his concern about how the neoconservatives use this “war as a pretext” (i.e. with a manifest lack of subtlety). ZBK fully endorses the belligerent strategy of the neocons; but he reproaches them for leading it so brutally, so directly, that it is perceived. His program: to do the same thing, but subtly, without it being seen. In Central Asia, for example, it proposes to support the Islamists, so that they oppose Russia’s return to the area – to instrumentalise Islamism, for BZK, is therefore not to fight it everywhere, but on the contrary to selectively promote it.

This strategy, which is infinitely more subtle than neoconservative brutality, is based on a priority given to influence, with open warfare coming only as a last resort. ZBK advocates in particular the infiltration of Eurasian elites, the detection of the members of these most influential elites, in order to favour them (by the media tool in particular), so that they become predominant within their specific oligarchy. Where neocons bomb and occupy militarily, ZBK proposes to corrupt, divide, manipulate, to subterraneanly impose governments at the behest of the USA. Thus, it will no longer be necessary to wage war against the enemy: it will have been conquered from within, by offering a fraction of its ruling classes integration into the emerging globalized hyperclass. The Obama administration’s apparent appeasement policy over the past year must be understood as part of this strategy.